Decades of rolling back big government didn’t go fast enough before mortality triggered the estate tax after all.

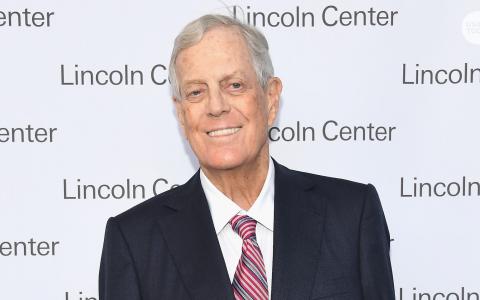

Paper magnate David Koch spent the better part of three decades hearing the ticking clock. He lived with death for a long time.

And as heir to one of the world’s great fortunes, he knew that when the clock ticked down, the estate tax would take a staggering amount of money away from his kids and hand it to the government he hated.

Most people who complain about policy never do anything about it. Fighting Washington is like fighting the weather.

But at the Koch family’s level, spending billions to change the tax code wasn’t just a statement of personal preference. It’s a practical decision to allocate the assets where they get the biggest possible return.

Unfortunately, David Koch ran out of time before that huge investment paid off. Let’s see where his heirs go now.

A question of scale

Koch and his brother Charles personally spent at least $100 million funding libertarian efforts to roll back what they saw as a bloated government apparatus.

That agenda included starving Washington by cutting tax revenue wherever possible. On that basis, if numbers are the only thing that matters, spending $100 million to protect what’s now a combined $100 billion is worth it.

Figure the estate tax liability on that fortune would have run to $70 billion in the late 1970s and the family would have come out ahead if they’d spent every cent of that money lobbying against the IRS.

Questions of public benefit and private burdens are completely separate at this stage. It’s pure calculus that anyone who advises an ultra-rich family needs to accept as part of the duty to achieve the best possible real outcomes.

Normally that means strategic contributions and shifting cash into vehicles with lower tax exposure. A mere billionaire might accumulate onshore and offshore trusts, establish offices in states and countries that avoid various forms of taxation and even engage in charitable and business activities with tax breaks in mind.

The Koch brothers started there. A lot of their philanthropy funds think tanks that argue for their vision of society, just like their medical and artistic donations support hospitals, museums and schools.

The difference is that at their scale, they could afford big enough think tanks to theoretically make a difference on their personal tax bills.

When $70 billion was on the line, it only took a 0.01% estate tax rebate to justify a $100 million investment. The odds of that minuscule level of success were high. It was a good bet.

Since then, the effort actually contributed to a 30 percentage-point rollback in estate tax rates. The IRS bill that would have cost them $70 billion at the beginning is now only $40 billion.

David Koch’s half of that investment applied against that liability generated nearly a 30,000% return. Fighting the tax code saved his heirs up to $15 billion.

Of course the estate still owes the IRS 40% of whatever the advisors were unable to protect. Dying with an estate tax on the books may ultimately cost David Koch’s family as much as $20 billion.

But anyone can die at any time. Even though the Koch brothers didn’t finish their campaign in David’s lifetime, the money was still well spent.

Partnerships and strategic risks

Detailed figures on what the Kochs actually spent are scarce because they worked together and brought in other sympathetic billionaires to achieve a shared goal.

The Koch “network” has spent a lot more than $100 million. Last presidential election cycle, they and their friends committed nearly $900 million to influence the national conversation.

Even if it was all Koch money, the return would still be huge balanced against the 30-point estate tax rollback. Stretch it across multiple family fortunes and the ROI is huge.

It’s simply in their best interest to spend a fraction of their money this way. Think of it as a form of risk management, buying a little IRS insurance now to reduce the liability at the end.

Of course not all ultra-high-net-worth families think this way. Quite a few are happy to leave the kids with a paltry $1 billion or so, leaving the rest to charities while paying whatever the government decides they owe.

The calculus here is both sentimental and pragmatic. The principals feel good about nurturing a traditional middle class so their kids can have a certain type of educational experience, make a certain type of friendships and ultimately live a certain type of life.

As far as they’re concerned, that’s worth paying higher taxes today in addition to making the usual donations to schools, art organizations and so on.

The government safety net itself becomes their charity in a real sense. And if that safety net works to make society stronger, future generations of heirs face fewer existential threats.

After all, happy people aren’t as motivated to hold the grandkids or join suicide cults. Whether big tax bills are ultimately cheaper than tighter security is an open question, but that’s how the theory goes.

Either way, every family decides. The Koch calculus goes one way. Someone like Warren Buffett or Mark Zuckerberg will come up with different conclusions.

The point here, however, is that the motives converge. Everyone wants a stronger future for their kids and the people around them. They just disagree on what that means.

Always a moving target

And perfection is always the enemy of progress. Nobody would say David Koch failed just because he didn’t live long enough to see the estate tax hit zero one more time.

For one thing, there are a lot of sweet spots in the tax code and getting the best possible return sometimes means sacrificing the estate in order to keep more money in the meantime.

The Koch brothers practically doubled their fortune since 2012. Go back to the 2008 bottom and they were maybe worth $20 billion put together.

A decade of strategic tax relief helped them accumulate a lot of wealth that would have otherwise gone back to the IRS year by year.

That’s an investment too. They didn’t get greedy or try to force policy. They kept it subtle.

It paid off big. The share of the business David now leaves his kids is 400% bigger than it was a decade ago . . . after taxes.

And needless to say, that money funds a lot of tax protection as well.

What does a $100 million estate plan buy? It’s a huge amount of money but again, the stakes here justify lavish expenditure.

Odds are good David Koch’s share of the company is shielded in any number of trusts and non-profit entities. Over the years, these structures have bled current cash away from what’s now become his estate.

They’re not individually huge. The David H. Koch Foundation, for example, is only worth $20 million right now. But every year, they got that cash out into the world.

That’s what matters. Besides, David’s widow is only 57. Whatever she inherits transfers free from tax until she herself dies.

That could be a long time away, and for all we know the tax environment will be very different then. As long as we’re alive, it’s always a moving target.