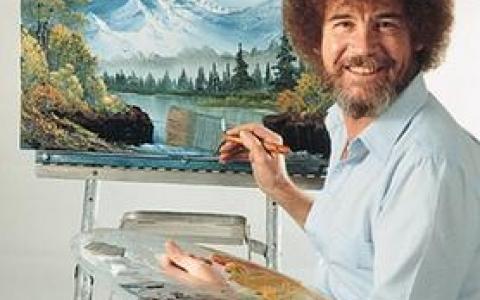

Bob Ross is everywhere these days: bobbleheads, Chia Pets, waffle makers, underwear emblazoned with his shining face, even energy drinks “packed with the joy and positivity of Bob Ross!” Whatever merchandising opportunity is out there, kitsch or otherwise, it’s a safe bet his brand-management company is on it—despite his having shuffled off the mortal coil more than 25 years ago.

He’s also a smash hit on social media, where he feels more like a Gen-Z influencer than a once semi-obscure PBS celebrity who rose to fame in the 1980s on the back of his bouffant hairdo, hypnotic singsong baritone, and a timeless message about the beauty of the world around us. His official YouTube page has logged close to half a billion views. He’s been satirized by the comic-book anti-hero Deadpool, the world-infamous street artist Banksy, and even Jim Carrey as Joe Biden on Saturday Night Live.

If that weren’t enough, he’s hawking Mountain Dew in a new CGI commercial that’s right on the edge of the uncanny valley, and Netflix has a feature-length documentary about him due this summer by the prolific actor-producer Melissa McCarthy.

Yes, Bob Ross is a beacon of light in an ever-darkening world—an endless stream of soothing bon mots perfectly at home in the meme-and-merchandise internet era.

He was also recently in federal court. Or, to be more precise, his eponymous company Bob Ross, Inc., was. Now run by the daughter of Bob’s original business partners—Annette and Walt Kowalski—Bob Ross, Inc., was defending itself against claims that it had made millions of dollars by illegally licensing Bob’s image over the last decade, expanding far beyond the company’s original core business of selling Bob Ross-themed paints and paint supplies.

The broad contours of the case revolved around the nuances of intellectual property law and were nothing new in the world of legal bickering over celebrity estates. The details, on the other hand, resided in the land of the unbelievable—incorporating deathbed marriages, last-minute estate changes, CIA-style tape recordings, and even a real-life former CIA agent.

It was all made even more bizarre by the plaintiff who filed suit: Bob’s very own son Steve Ross, a long-standing superstar in the sub-universe of Bob Ross fandom who had largely dropped off the face of the Earth after his father’s death—and was even rumored to have met his own demise some years earlier.

Stranger still, it wasn’t the company’s first brush with federal and other lawsuits. Although, under the leadership of the Kowalskis, Bob Ross, Inc., was usually on the delivering, rather than receiving, end of said lawsuits.

In fact, in the months immediately following Bob’s death in the summer of 1995, Annette and Walt had launched a series of lawsuits and financial claims against Bob’s estate, his widow, his half-brother, and a dermatologist in Indiana who moonlit as the writer-producer of a short-lived PBS children’s show about a talking tree in which Bob had posthumously appeared.

All in all, the strategy was designed to gain total control of Bob’s afterlife—despite Bob’s clear intent otherwise. One of Bob’s close friends took to calling the effort “Grand Theft Bob,” and for 25 years, until now, the story has been known only to a handful of people who were often too scared to speak lest they, too, be the subject of a well-financed lawsuit courtesy of Bob Ross, Inc.

The following account is based on primary documents and interviews with more than 30 people who knew Bob personally or worked alongside him in the hobby-art industry—including family members, fellow TV artists, business associates, and competitors.

Read the rest of the story on The Daily Beast.