How Can Investors Avoid Procyclical Behavior?

One of the more well-known social aspects of investing is the behavioral challenges we face, both as investors in individual stocks as well as at the portfolio level. For instance, when a stock has performed well, we are tempted to assume its prospects are improving and we tend to nudge up our fundamental estimates. When the stock is a laggard, we might start to lower our expectations to fit the market’s pessimism. This is called recency bias because we tend to more easily recall the recent past than we do other information. Biases like this can let price—rather than an asset's fundamental characteristics—dictate the investing narrative. This leads to procyclical behavior—buying after (and often because) something's gone up, or selling after (and often because) something's gone down.

This phenomenon is universal across investing, not just stock investing. We also know this behavior as performance chasing.

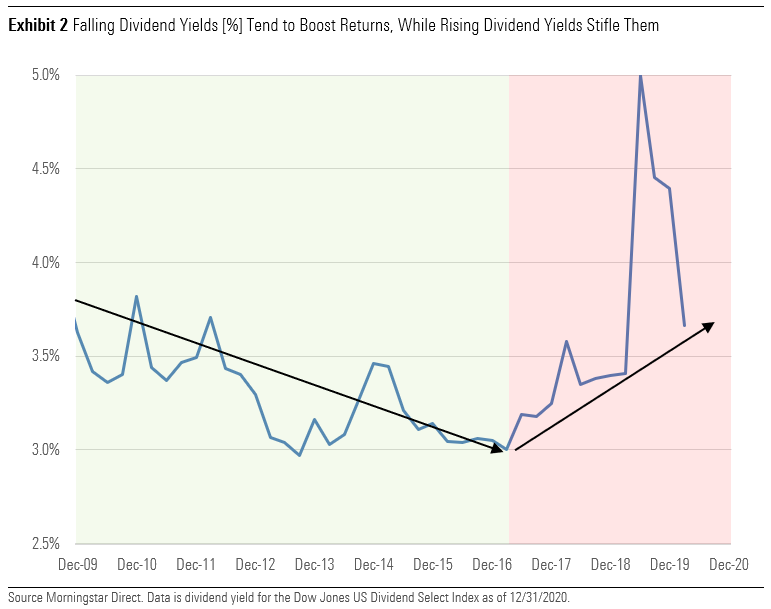

How do we keep ourselves and our clients from mistakenly bailing on a stock or strategy when performance has suffered? Speaking from experience and first-hand accounts, the strategy I now manage hit such a rough spot a few years ago. After a number of years of strong performance, the tide turned. Inflows became outflows. Advisor cheers turned to doubts. What changed?

I came aboard to manage our Dividend Select Equity Portfolios in August 2018, near the nadir of underperformance. In my estimation at the time, the portfolio was sound. Many of the same companies that had driven upside in years past were still owned and the underlying businesses were performing as well as ever. The difference was the market’s appetite for these companies, that is, valuation. Staying the course by maintaining positions in high-quality, wide-moat businesses—sticking to the strategy's design—is usually the best call. And in this case, valuations slowly recovered and performance improved.

Understanding Opportunities

So again, how can investors know when to stick it out and when to realize it's time to sell? We believe the answer lies in focusing on fundamentals while keeping a close eye on valuation. Doing so can give us a better understanding of the drivers of return, which in turn can help us know when to stay the course and when to chart a new one.

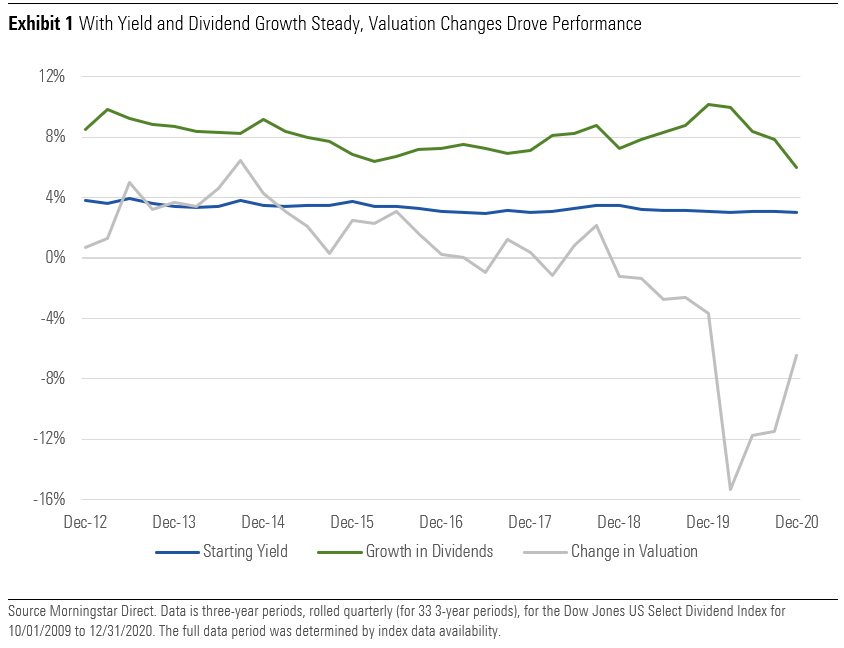

Being valuation-driven investors, we are acutely aware of how valuation, or more specifically, the change in valuation, will impact our returns. Ignoring these impacts can have serious consequences for investors. Finding a company whose stock has a well-covered dividend yield and accurately estimating an entity's long-term growth isn’t enough to fully understand the potential reward and risks in owning a security. Evaluating the components of total return—including expected changes to valuations—can help investors to take advantage of market opportunities and to stay the course when necessary.

Valuation Changes, Illustrated

To demonstrate, below we evaluate rolling three-year performance of a broad-market dividend index, the Dow Jones US Select Index, over the 11.25 years ended Dec. 31, 2020,1 to identify attribution of the various components of total return. In summary, we found:

- Starting yield was always positive and fell in a range of roughly 3%-5%.

- Three-year compounded annual growth for dividends was positive for all three-year periods, and growth ranged between 6%-10% annually.

- The contribution from change in valuation had the widest range, oscillating between positive and negative and going deeply negative during the height of the COVID-19-driven market panic.