Since I woke up this morning, I’ve received 30 mobile news alerts, 25 email alerts, and another 17 emails from investment managers providing their unsolicited views of the financial world. My Twitter feed provides constant updates on investment news and stock market fluctuations. Meanwhile, cable financial and news channels produce 24/7 streams of financial information, with chryons and news alerts scrolling across the bottom of the screen.

It seems like having so much up-to-the-second financial news at our disposal would make us better investors. But that’s not necessarily true. About a decade ago, I weaned myself off this daily deluge of data when I realized that most of it was noise. All that information took a lot of time to keep up with, skewed my view of the world, and didn’t make me a better investment advisor. Now I don’t check the stock market every day. Sometimes I even go weeks without looking.

Given the limited amount of information our brains can process, we need to prioritize quality over quantity. It is easy to be wowed by investment pundits who can cite all sorts of facts and figures about the stock market and the economy. So, how do we determine which of it has value?

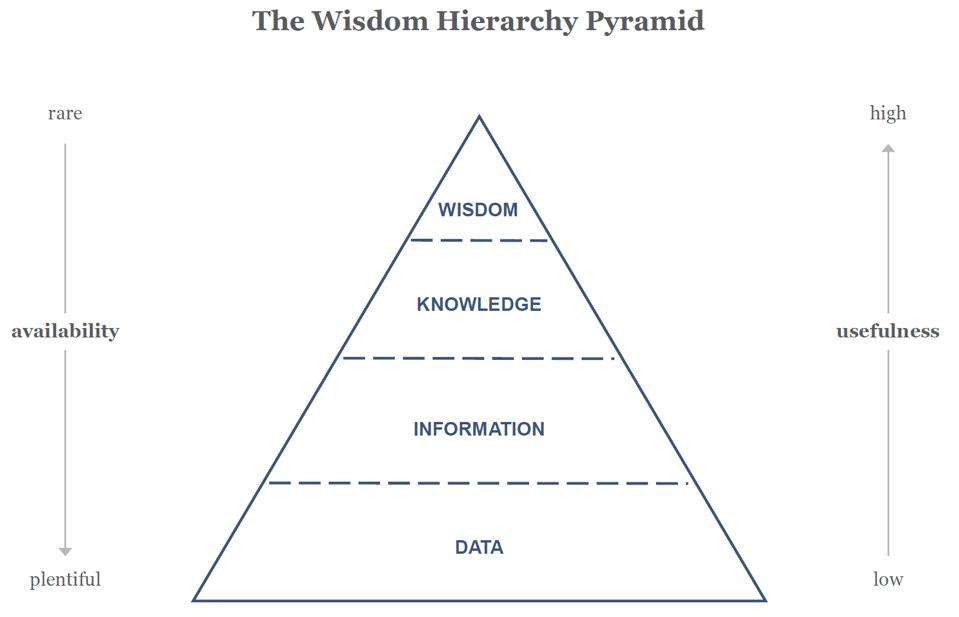

To answer that question, I look to the wisdom hierarchy, a concept developed by organizational theorist Russell Ackoff in 1989. In this model, Ackoff divides the types of things we hear and learn every day into four categories: data, information, knowledge, and wisdom. Then he ranks them in order of usefulness and availability. As the shape of the pyramid below illustrates, wisdom is the most useful and rarest kind of input, followed by knowledge, information, and data – the least helpful and most plentiful.

Data, Information, Knowledge, and Wisdom Defined

A key to making sound investment decisions is to base more of our choices on wisdom rather than knowledge, information, or data. But to do that, we must first understand the difference:

- Data is raw facts, events, experiences, and observations. Examples include housing starts, stock prices, weekly unemployment claims, and interest rates.

- Information is data that has context. For example, housing data becomes information when it’s organized by region and price because it indicates which segments of the housing market are doing better than others. Stock prices become information when their quarterly returns are listed by industry in an investment report because it shows which types of companies are performing best.

- Knowledge is data or information coupled with experience, understanding, and expertise. For example, an economist armed with housing start information can tease out insights about the overall state of the economy. Likewise, a financial analyst can look at the quarterly stock returns by industry and combined with other information understand where we might be in the market cycle.

- Wisdom is knowledge applied with judgment earned through direct experience. In his seminal 1989 paper on the wisdom hierarchy, Ackoff defined it as “the characteristic that differentiates man from machines.” For example, if an expert concludes that the stock market is becoming overheated based on various measures, a wise investor knows the market almost always overshoots reasonable valuations on the upside due to ingrained human biases and takes a long-term view.

What Investment Wisdom Sounds Like

When you view the investment industry through the lens of the wisdom hierarchy, it becomes apparent that most of the expert opinion we read in the news or hear on TV isn’t wisdom but mere knowledge or information. Wisdom is a rarer commodity that often sounds simple but isn’t easy to implement because it runs counter to our instincts and emotional reactions.

Warren Buffett’s advice that investors should “be greedy when others are fearful and fearful when others are greedy” is investment wisdom because it is timeless guidance that is correct in most circumstances. But this wisdom can be hard to act on because it requires swimming against the tide: buying when the market is crashing and selling when it is booming.

For the same reason, Rule 9 of Bob Farrell’s 10 Market Rules to Remember is also wisdom: “When all the experts and forecasts agree, something else is going to happen.” We all chuckle at the truth of this statement, but actually investing in ways that ignore the consensus can be downright scary.

The Wisdom Hierarchy in Action

The financial world is awash in investment data, information, and knowledge. Although wisdom is harder to come by, you can find it by taking the following actions:

1. Use the wisdom hierarchy to focus on what’s most important. Researchers at the University of Queensland in Australia found that study participants who had to consider five or more variables to reach a solution were more likely to give the wrong answer. Exposure to lots of information causes our brains to “revert to a simplified version of the task that does not take all aspects into account.” To avoid overload, we must tune out information that lacks value.

2. Read investment books instead of financial news. Because of their length and depth, books are good sources of knowledge and wisdom. That’s why I scan the news but spend more time reading investment books. These five investment books are chock full of wisdom.

3. Understand the key characteristics of wisdom. Financial advice that rises to the level of wisdom has a pure, timeless quality that can feel dull and unsatisfying in the face of life’s challenges. As Wall Street Journal columnist Jason Zweig explained when asked to define his job at a journalism conference:

“My job is to write the same thing 50 to 100 times a year in a way that neither my editors nor my readers will think I am repeating myself. That’s because good advice rarely changes, while markets change constantly. The temptation to pander is almost irresistible. And while people need good advice, what they want is advice that sounds good. The advice that sounds the best in the short run is always the most dangerous in the long run.”

Wisdom usually sounds obvious; when you hear it, you think, “of course.” Yet, it’s still hard to follow because our emotions often get the better of us. Those willing to stay the course might come to appreciate this wisdom from Rob Arnott, head of Research Affiliates: “in investing, what is comfortable is rarely profitable.”

This article originally appeared on Forbes.