Trust experts weigh in on the details of Jobs’ trust and estate plan. The private but methodical technology innovator went well outside the box to ensure that his $6 billion legacy was as perfect as the technology he created.  The empire that Steve Jobs built from garage start-up to $342 billion behemoth now has to find its own direction, but his personal legacy is most likely evolving according to an extremely sophisticated plan.

The empire that Steve Jobs built from garage start-up to $342 billion behemoth now has to find its own direction, but his personal legacy is most likely evolving according to an extremely sophisticated plan.

First things first: nobody we talked to expects his estate to pay a penny in estate tax, no matter what the official rate happens to be.

And while Jobs might easily have been worth over $6 billion when he died at age 56, don’t hold your breath waiting to see who he remembered in his will, estate planners say.

“It wouldn’t surprise me if unlike most other celebrities, Steve Jobs did things correctly and there is no will to be read,” says Florida estate attorney David Goldman. “Privacy was such a big part of his life and his career,” he adds. “And if everything passed through one or more trusts, there would have been no probate fee.”

Reverse-engineering the masterpiece

Jobs had foresight as well as genius on his side. He’d been diagnosed with cancer back in 2003 -- almost exactly eight years before it killed him -- and at the time, the prognosis was 50/50 that he wouldn’t live beyond 2008.

That gave him a lot of time to reflect on his own mortality and his advisors plenty of warning to make sure his assets end up exactly where he wanted them to go.

Given his efforts to keep his personal life private, we won’t ever know exactly how his estate plan allocates his wealth -- unless, of course, he wanted the world to know.

We do know that it involved a network of at least two trusts. California records show that he and his wife, Laurene, moved their Palo Alto house and other real estate into two trusts when his liver was failing in early 2009.

Despite speculation, the immediate motive here was probably not to avoid probate or taxes on that joint property, since it would have passed to her without much fuss in any event.

And while the house is nice enough, it was hardly a billion-dollar mansion, so it’s more likely that Jobs’ accountants and lawyers were really more interested in clearing the decks as part of a bigger move.

Completely under the radar, SEC filings reveal that Jobs was also busy moving the rest of his material wealth -- 5.5 million shares of Apple stock and 138 million Disney shares, a memento of his other baby, the animation company Pixar -- out of his estate and into a trust.

Since he basically earned nothing from either Apple or Disney since then, it’s possible that he died with no real assets in his name, achieving David Goldman’s zero-probate scenario.

The biggest questions remain

In life, Jobs still controlled that $6.4 billion mountain of stock. What we don’t know is what goals his lawyers built the trusts to achieve and who the trustee is now.

After being abandoned as a baby, he wasn’t a fan of inherited wealth, so a dynastic arrangement designed to look out for his four children and their descendants down the ages looks unlikely at best.

However, since Jobs had a daughter from a previous relationship, such a “nobody inherits” strategy would avoid family conflict by putting everyone on the same footing, estate planners say.

“His life was complicated,” says Bernie Vogel, CEO and head of Silicon Valley Law Group’s estate planning group. “From a fundamental perspective, they have to have looked very carefully at that aspect of his legacy.”

A philanthropic enterprise of some sort may be on the table, but we can only speculate on what causes Jobs would have wanted to fund.

When he was younger, he donated plenty of money to progressive causes, starting a short-lived foundation for entrepreneurs back in the late 1980s.

But in the last few years his inability to make the kind of showy bequests that Warren Buffett, Bill Gates and other billionaires were making raised eyebrows.

Privacy is often cited as the motive, but he might not have actually had the cash. Since coming back to Apple, he took next to no salary and deliberately passed on the $150,000 to $500,000 a year that other Disney board members were voting themselves.

And since he never sold a share of stock, all his wealth -- and now his trust’s -- remained locked up in the companies he built.

Silicon Valley attorney Nancy Chillag wouldn’t be surprised if his money will go to help other technology start-ups, effectively creating a “think different” angel capital fund.

"What he should have done with his money is form a foundation to support creative kids with big ideas who are just one invention away from changing the world the way he did,” she says.

The book will provide clues

His self-titled autobiography comes out in two weeks, so it might provide big clues to the legacy he wanted to leave behind.

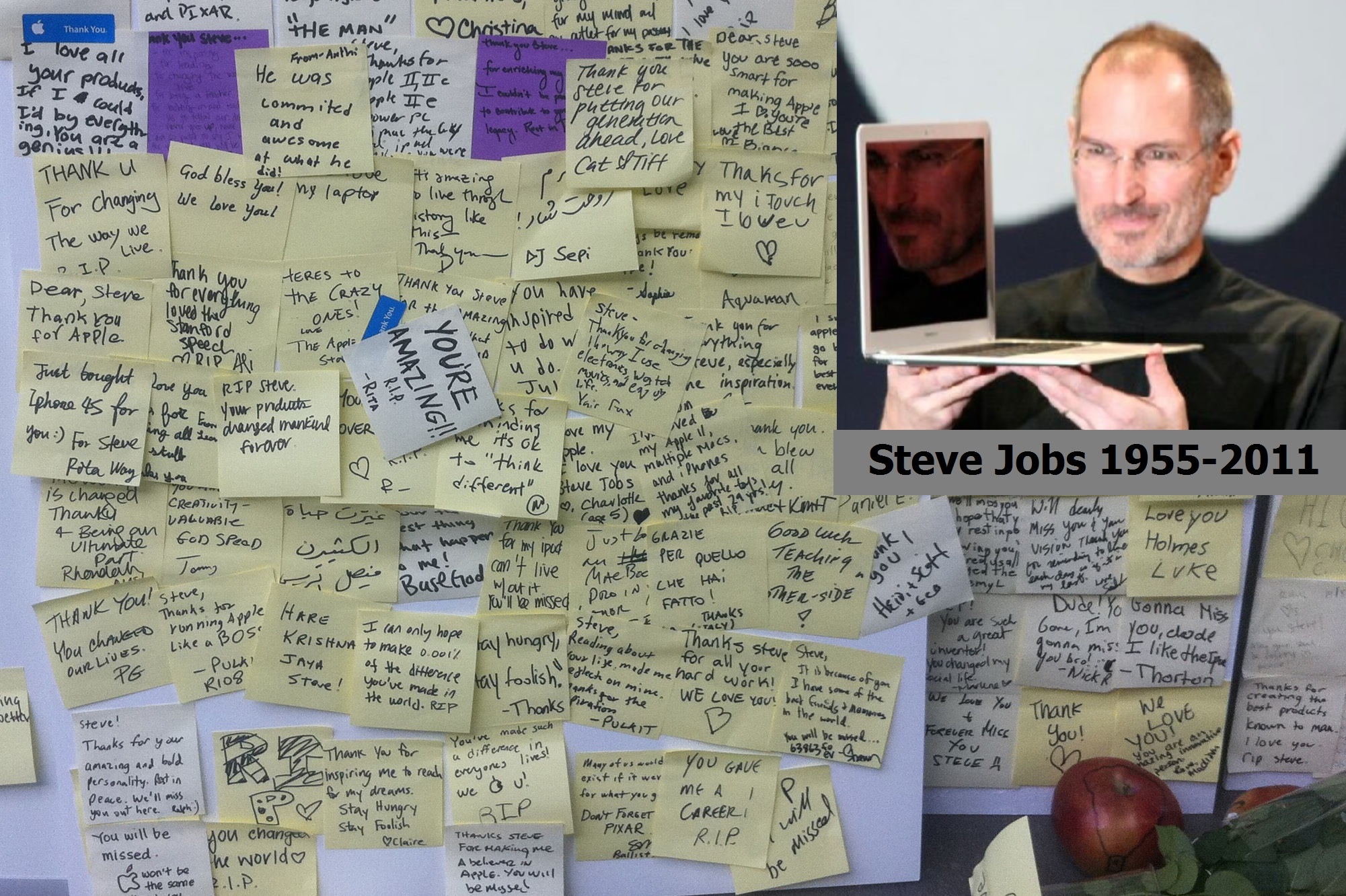

It’s also the top seller on Amazon even before its official release: proof that Jobs’ cult of personality was a bigger asset than all his shares put together.

The intersection of media rights and technology probably figured heavily into the estate plan, Bernie Vogel says.

“With the following he had and the computer graphics we have now, his image can remain active as long as people think fondly of him,” he notes. “He can announce a product at the next MacWorld.”

Jobs reportedly left a four-year plan for Apple behind, so such "announcements" are a possibility. Beyond that, it's likely that he worked with his advisors to lock down exactly what that image can and can’t do in the digital future to come.

“You become self-aware about your place in history when you’re dying,” Vogel sums up. “But your publicity rights, your personality, your media image are part of your legacy that simply passes to the next generation unless you’re careful.”

“The kids might want to honor his wishes, but unless the intangible rights are addressed in the estate planning, sooner or later someone will want to use his personal brand to make money.”

Scott Martin, senior editor