Sometimes the principal is the factor that holds the wealth creation process back. Removing him or her from the mortal calculations can have surprising results.

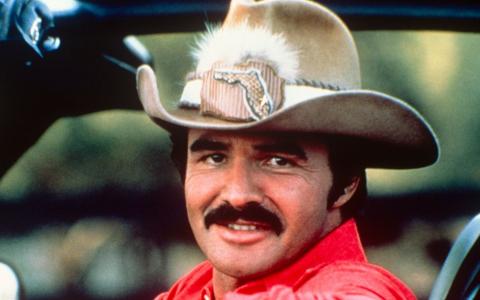

Burt Reynolds was cantankerous, willful, whimsical and occasionally tested the line of self-parody. That was his charm, his gift and his most formidable career asset.

In short he was a human being who showcased every tic of the human condition across close to six decades in Hollywood.

It was an accident. He was originally going into law enforcement. But it made him a legend. Occasionally it even made him rich.

Now that death has taken him out of the loop, it’s going to be very interesting to see what his heirs make out of the legend.

Like any other client

Burt probably didn’t die “broke” but by today’s Hollywood standards his assets ended up on the modest side.

Maybe he had $3-$5 million left when he died last week at 82. That’s exactly in the sweet spot of what most people consider comfortable — enough money that the basic bills get paid, not enough to feel invulnerable.

He apparently lived rent free in his Florida hideaway since selling the property in 2015. That transaction freed up $3 million for living expenses. Think of it as a form of equity cash-out, with posthumous foreclosure as the goal.

As quietly as he lived, that cash was probably more than enough to stretch across the years he had left. That lends support to his claims that he was only selling off memorabilia to free up space and not because he needed the money.

Likewise, while he kept working throughout his life, most of the recent roles were stunt cameos, the kind of wink TV appearances that keep paychecks coming but don’t really build wealth.

That’s okay. A lot of actors keep working until late in life. (Investment managers do it too, and for that matter so do a lot of once-highly-compensated retirees.)

But like many of his contemporaries, these Old Hollywood numbers look small, even compared to what Burt had to work with early on.

He was making $5 million a picture in the Cannonball Run years, an era when that amount of cash could credibly budget an entire film. That was what the king of the world earned in the mid-1980s.

And he worked a lot. Not constantly, but enough to theoretically seed a significant fortune later in life.

Easy come, easy go

Like a lot of people, he blew most of it on vacation property and alimony — two expensive examples of the heart wanting what the balance sheet can’t really justify.

The first divorce was early. She got the Gunsmoke money and the house.

Thirty years later, Loni Anderson was harder. He was in his late 50s and eager to slow down. His money was tied down in heavily leveraged ranch land and doomed country cooking restaurants.

Even after a bitter legal fight, she only ended up with a lump sum of $300,000 and $15,000 a month in support for herself and their infant son Quinton.

Half of that money only materialized when Burt finally sold the house three years ago. It took him two decades and two bankruptcies to get there.

And there’s no shame in any of this. It’s just how life goes.

He took a chair in the mouth on a film set and spent years on painkillers while dentists did their expensive work.

When his second marriage melted down, he got depressed. He wasn’t as eager to take on new roles — at exactly the moment he needed cash flow to make alimony and rebuild his own financial position.

Even the rebound girlfriend took him to court for a settlement. Naturally he got behind on the taxes and filed for bankruptcy protection again.

A more organized or financially oriented star wouldn’t let any of that happen. There would have been ironclad prenuptial contracts, better due diligence on the investments, someone to say “no” to sinking more millions into more acreage.

He would’ve had a professional advisor. Hollywood has gotten a lot better at bringing real expertise to the team, but it’s still a matter of luck all too often.

Corporate executives paid less bring in professional help and retire with a lot more.

Beyond “The End”

One of my favorite Burt Reynolds movies is of course suicide comedy “The End.” It gets a little dark. It’s hilarious.

But he made it early on, and that’s the nature of celebrity now. Death is only the first step when it comes to liberating fame and its cash-generating power from the living person.

Burt never really cashed in. He didn’t build production companies and so his heirs — likely son Quinton — won’t own any of his most famous movies.

As far as he was concerned, these movies were just paychecks, a lucrative way to spend a few months in the fresh air. They weren’t “intellectual property” to be collected and monetized.

But there are still some assets for the estate to exploit. There’s the name, the mustache, the T shirts.

Last time I checked, he owned 25% of his TV show “Evening Shade,” which wasn’t always considered a hit but it ran four seasons.

It’s not on iTunes. I can’t find it streaming on Amazon or Netflix. Nobody’s monetizing that show.

Quinton or his advisors could start there. A lot of profitable entertainment companies launch with a modest bundle of rights. If there’s money left in those episodes, the professionals will find it.

Burt showed zero interest in making it happen. Maybe they tried. Somehow I don’t think so.

Either way, they didn’t try it now, when the nostalgia engine is revving fast. If Burt had been a more serious singer, his album would be rocking up the charts now.

As an actor, it’s a lot less clear. A new generation streams his movies to see what the fuss is all about, but his estate might only see a flicker of residual income at best.

Quinton is barely 30. He might have big plans for a family legacy. Supposedly he and his dad were estranged for a long time.

Burt’s gone but the business of Burt Reynolds is still a work in progress.

The estate won't laugh any more. But if it's all about cash flow, it's free from all that now.