I’m sitting in Comfort-Plus on a long, completely full, and overbooked flight as all the passengers in my row are sharing squirts of hand sanitizer. Welcome to coronavirus travel. The possibility of widespread illness is frightening, but when the market hit an all-time high on February 19, 2020, and follows that with the worst decline since 2008 in just nine days, and then on March 2, 2020, posts the biggest one-day point gain in history, we can’t help but take notice. What should investors do to protect their 401(k) or IRA?

First, let’s try to put the scare in focus and start with a problem in the math. The Covid-19 coronavirus started in China, where it has infected at least 80,000 people and killed about 2,800 people. Note the phrase ‘at least.’ I question the coronavirus (or media’s) math. We know the number of diagnosed cases; let’s call that ‘c.’ We also know how many people have died; let’s call that ‘d.’ The media’s math is too simple, deaths divided by diagnosed cases, computing a mortality rate of 2%. A more correct statement would be ‘the mortality rate on diagnosed cases of coronavirus is 2%.’ We have no idea how many people are infected with Covid-19. We only know that in China at least 80,000 have had it, and about 2,800 have died. For all we know, a million or ten million could have the virus, and we still have 2,800 deaths. We should look at the mortality in terms of diagnosed cases, not population.

Second, enter the ‘Baader-Meinhof’ phenomenon or familiarity bias. Named for the notorious East German terrorist gang from 1970, no one had ever heard about them until they hit the media, then suddenly, they were everywhere. Similarly, until a few months ago, no one except a handful of infectious disease specialists and scientists even knew or cared about coronavirus. Now, everyone is talking about it. There are hundreds of types of coronaviruses, and many of us have had them, usually resulting in a cold. More insidious forms can attack other body systems, like MERS or SARS, and are quite serious. This new one is a novel form of coronavirus, dubbed Covid-19. It incubates in about 2-14 days (and unfortunately, victims are asymptomatic during incubation). According to the CDC, the influenza virus in the 2019-20 season affected between 19 and 25 million people and caused up to 25,000 deaths. The difficulty is that we can’t tell a mild case of Covid-19 from the flu. Thus, we don’t really know how many people have it, or how virulent it actually is.

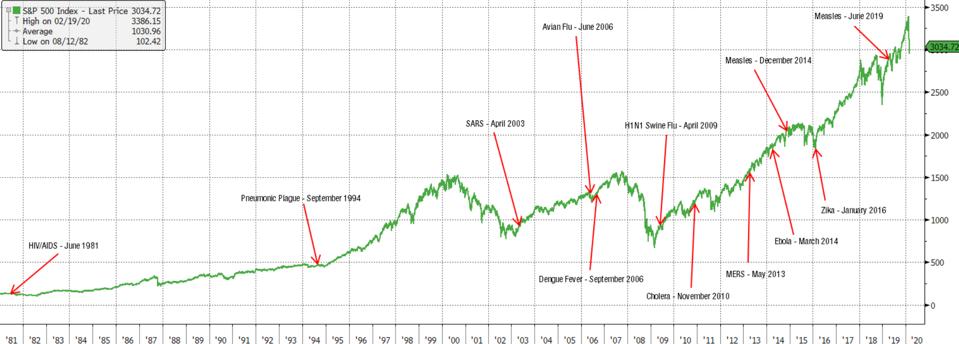

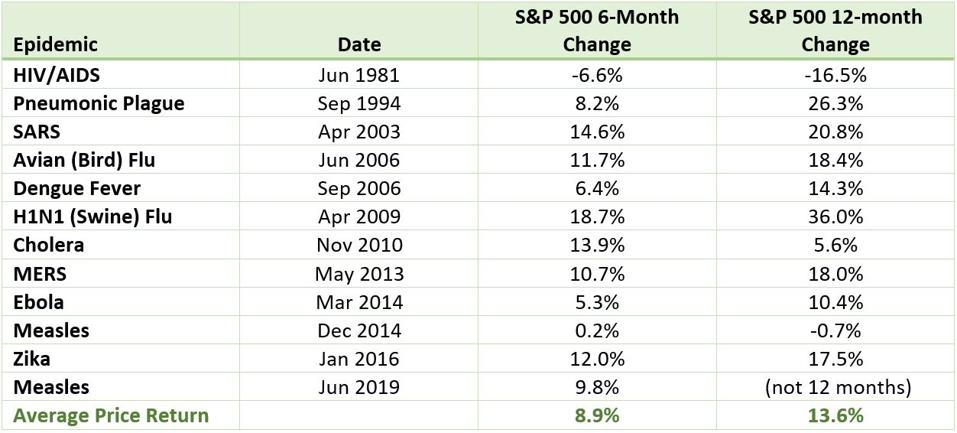

What we do know is that there is significant media coverage and public effect. China effectively shut down the city of Wuhan; cruise ships have been quarantined, and study abroad sessions have been canceled. We have a reactive slowdown that is decelerating the global economy. PGIM estimates a -4% drop in China’s GDP and the first Quarter 2020 global GDP as about 0.8% lower. Lower GDP means lower profits, and lower profits mean lower stock prices. Hence, the rapid decline in global equities. We might want to note that all prior epidemics have, in fact, ended. Here’s a nifty look at market performance over the last 40 years, and the incidences of widespread/epidemic illness. The information on disease outbreaks is courtesy of the World Health Organization’s Disease Outbreaks by Year Archive:

Using the information from the preceding charts, we can conclude that the average price return for 6-months and 12-months is positive by 8.9% and 13.6%. Note that there was only one (minor) negative 12-month return following an outbreak. The chart also illustrates that the market tends to shrug off epidemics after a while.

Armed with this information, there are five choices you can make regarding your holdings:

A. Do Nothing

B. Buy

C. Sell

D. Tactically Rebalance, or

E. Strategically Rebalance

Do Nothing. This would be a good name for a political party (appropriately, there was one called the ‘know nothing’ party). Doing nothing would mean keeping your portfolio exactly as it is. From the history above, we can surmise that this could be a good strategy. Staying put in the past during downturns has been a successful strategy.

Buy. This is an opportunistic plan. Here, you might buy select sectors, funds, or stocks. There are a variety of opportunities: contrarian, where you would buy the most beat-up sectors (e.g., airlines, oil); aggressive, where you would see the solutions (e.g., biotech with Covid-19 vaccine), or ‘sale’ where good stocks in normal industries are down (e.g., consumer products, paper, telecom, power).

Sell. Selling equities is a defensive plan which works if you successfully predict that the current downturn is actually the beginning of a much longer and more serious slide in equities. It’s a possibility, but again, the evidence from the chart seems to indicate otherwise. The issue with the sell strategy is that it appeals to our most basic human nature that long predates the existence of markets: the fight or flight syndrome. On the other hand, as this Covid-19 situation has evolved, the bond market has rallied. Selling bonds would produce a profit. Consider the old adage: ‘buy-low/sell-high.’

Tactical Rebalance. A tactical rebalance happens when you buy and sell at the same time. You may have your 401(k)/IRA in 60% equities and 40% bonds. You may decide this is an equity buying opportunity and bond selling opportunity, so you switch to 70% equities (buying more stocks) and 30% bonds (selling bonds). This is a rebalance with a shift.

Strategic Rebalance. This is a simple strategy in which you reset your allocation back to where it was. So, if you were 70% equities and 30% bonds on February 19, and now you are about 61% equities and 39% bonds, you simply reset and sell some bonds to buy stocks. There are multiple studies that show rebalancing reduces overall portfolio volatility.

Bottom Line: It pays to put things into perspective. Besides Covid-19, there are other significant factors acting upon the markets, a significant election and the Federal Reserve, trade deals with the European Union and other countries, and geopolitical risk, to name a few. Now is a great time to review your portfolio and consider the options available to you. If, after some research, you are uncertain, history also seems to demonstrate that it doesn’t hurt to stay put. Ironically, ‘don’t just do something, stand there,’ seems to be sage advice.

This article originally appeared on Forbes.