(Bloomberg) - As markets staged a monster rally following the Federal Reserve’s shift toward loosening monetary policy, one corner of the financial system had reason to remain on edge.

For participants in the overnight funding markets — a key conduit for bank borrowing and linchpin for determining interest rates — Wednesday’s policy meeting contained a more pertinent message from Chair Jerome Powell than the one that sent stocks soaring and pushed the 10-year US yield below 4%: namely, that the Fed’s balance sheet reduction would continue as planned.

A debate is simmering over whether the Fed is misjudging how far it can shrink its balance sheet — a process known as quantitative tightening — without causing dislocations in places like the repurchase-agreement markets, part of the essential plumbing of the financial system. Recent stresses there caused one benchmark rate to hit an all-time high, evoking memories of September 2019, when a different overnight market rate soared five-fold to as high as 10% and the central bank was forced to intervene.

The latest disruptions were indeed of a much lesser degree than four years ago and required no intervention, but both episodes shine a light on the increasingly delicate balance between the Fed, banks and other institutions that helps keep the overnight funding market functioning properly. Four years ago, increased government borrowing exacerbated a shortage of bank reserves that was created when the Fed cut back on Treasury purchases. Now, reserves — the financial “grease” that ensures markets don’t seize up and send rates soaring — and the level at which they become scarce is again in question.

Powell signaled on Wednesday that he was comfortable with the current level of reserves and said the central bank would slow or halt balance-sheet reductions as needed to make sure they remain “somewhat above” a level the Fed considered “ample.” The problem is, it’s unclear what that level is.

“I would be pretty humble because we don’t know,” said former Fed Governor Jeremy Stein, who’s now an economics professor at Harvard University. “Before you bump into the wall it’s very hard to gauge, rather than trying to reassure people we know what we’re doing and can play it pretty close.”

The central bank is keen on shrinking its balance sheet back to the smallest possible level without causing dislocations or derailing its broader policy goals. But this quantitative tightening, or QT, is happening at a time when banks that would normally pick up the slack in the vital funding markets are in less of a position to do so because of post-crisis regulations and for other reasons.

In these funding markets, investors — including banks, hedge funds and money-market funds — make overnight loans collateralized by instruments like US Treasuries. Where these rates trade largely depends on supply-and-demand dynamics, that is, the balance between the amount of cash in the market versus securities available. Overnight rates are largely stable as long as the amount of reserves in the system remains abundant.

It’s hard to make the case that reserves are scarce at the current level: There’s still just under $800 billion stashed in the Fed’s overnight reverse repo agreement facility, or RRP — a source of excess liquidity where counterparties like money-market funds can park cash and earn 5.3% — and banks are still sitting on roughly $3.5 trillion of reserves, which is well above where they were when the central bank began its latest round of quantitative tightening in June 2022.

Yet there are signs that financial institutions are safeguarding their cash cushions.

“We agree that the total amount of liquidity in the system is abundant,” said Mark Cabana, head of US interest rates strategy at Bank of America Corp. “We only have confidence that there’s excess sitting in the reverse repo facility. We’re less confident about the abundance of reserves in the banking system.”

Wall of money

During the Covid-19 pandemic, the Fed bought roughly $4.6 trillion of Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities to keep longer-term interest rates low and stimulate the economy. The process created a wall of money that needed to get deposited somewhere, leading to ballooning excess liquidity in the form of reserves and balances at the RRP.

To shrink its balance sheet, the central bank since June 2022 has been rolling over some of the bonds on its balance sheet at maturity without replacing it with other assets. The government then “pays” back the maturing bond by subtracting the sum from the cash balance Treasury keeps on deposit with the Fed — effectively making the money disappear. To meet its spending obligations, the Treasury needs to replenish its cash pile by selling new debt.

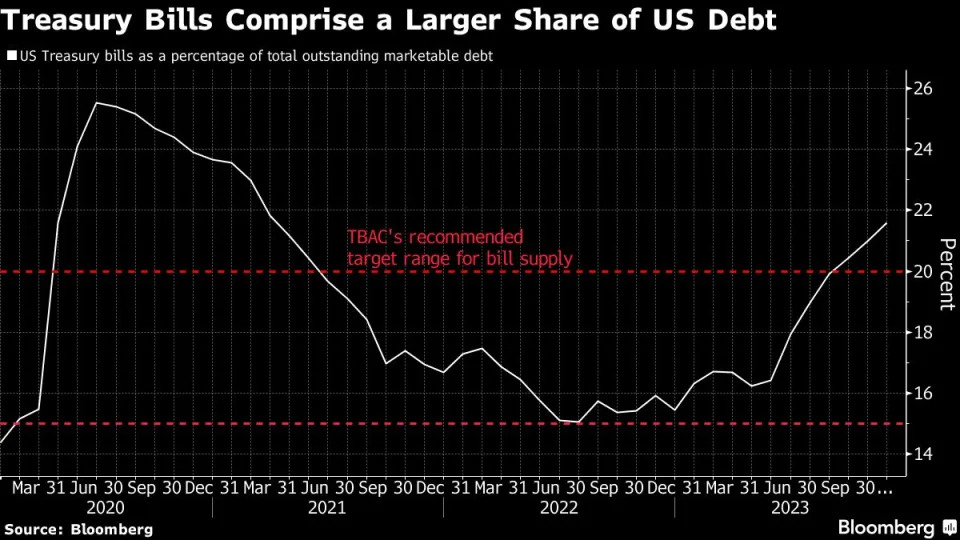

The Treasury has increased its reliance on bills for borrowing since June, and now the percentage of total outstanding debt is about 21.6%, which is well above the target range recommend by a group of bond market participants that counsels the department. By offering money-market funds an alternative to the RRP, the supply of bills has had the effect of draining the facility.

Meanwhile, there’s been a change at banks. At the onset of QT, lenders were comfortable shedding deposits. That’s because institutions had amassed trillions of dollars during the pandemic, they didn’t mind seeing a lot of that leave once the Fed started raising interest rates in March 2022.

That seeming apathy was shaken in March 2023 when the failure of California’s Silicon Valley Bank and other institutions — and realization that customers could earn more yield on their cash elsewhere — spurred depositors to pull trillions from the banking system and shift to alternatives like money-market funds. While the banking system has stabilized, that has come at a cost since institutions have had to increase rates on certificates of deposit and other products to retain that money.

And unlike during the 2017-2019 round of QT, when the pace of interest-rate hikes was slower, banks weren’t sitting on large unrealized losses in its securities portfolios. As the Fed grew its balance sheet during QE, commercial banks bought a lot of Treasury and agency debt when yields on long-term government debt were well below 3%.

Because institutions are still holding these sizable losses, any attempts to sell securities to raise liquidity will deplete capital and be viewed negatively by the market so they may want to hold more cash as a buffer, according to Bank of America.

“That’s a really important difference about why banks are demanding liquidity today and why they’re demanding more than they thought,” BofA’s Cabana said.

That means that if balances at the reverse repo continue declining, the Fed could find itself halting its balance sheet runoff earlier than expected, particularly when the RRP is completely empty, which Barclays estimates could be as early as May or June. Powell on Wednesday acknowledged that as the RRP leveled off, bank reserves would likely go down.

Myriad Wall Street strategists and even Fed policy makers say the central bank is a ways away from reaching that moment when it determines that reserves are at the lowest comfortable point — plus a buffer to guard against potential turmoil. But they don’t have a definitive answer on what that point is.

It’s “still far off in the future,” New York Fed President John Williams said last month, speaking to reporters after a speech. “We want to make sure ample means really ample. It’s hard to predict where ample reserves is.”

This unknown, coupled with the latest Fed-induced rally across US Treasuries, increases the chance of further tremors to the dollar funding markets, especially heading into year-end when banks face regulatory balance-sheet constraints. That’s because long positions — or bets on lower yields — need to be financed in the repo market, and so spikes in overnight rates could be a recurring issue the more crowded market positioning gets, according to Barclays.

“There will definitely be guys caught off guard,” Victor Masotti, director of repo trading at broker Clear Street LLC said.

Alexandra Harris