(Jerry Wagner, Flexible Plan Investments) I sometimes hate the term “active management.” It’s not because I have become a “buy-and-hold” convert, but because the term has been so corrupted by the financial-services industry.

Today, firms that are basically closet indexers use the term “active management.” Other advisers that simply tweak their portfolios occasionally proclaim they are “active managers.”

Even index funds have become active managers. They change the components of their indexes yearly. They appropriate active management methodologies and use terms such as “factor investing” to be called an index and avoid being viewed as active.

These so-called indexers want to have the benefits of active management while calling themselves indexers. It’s a “chicken-and-egg” kind of argument. Except, in this case, those of us who have been in the industry long enough recognize the repackaging of the original active management methodologies that came first.

“Dynamic risk management” vs. “active management”

So instead of “active management,” I proposed a different phrase to describe what it is that our investment firm does. Since 1981, we have been, and continue to be, practitioners of “dynamic risk management”: “dynamic” because of our ability to take action at any time, not just quarterly or at the end of the year, and “risk management” because the dynamic actions we take are done to manage the risk of the investment.

How does this differ from “active management”? Historically, active management has been divided into two camps: one that pursues market-beating returns in the short run, and one that seeks to reduce the risk of investing by avoiding the big drawdowns that occur periodically in all of the financial asset classes in the long run.

The first camp has generally been discredited. The indexers and the Morningstar-like financial press love to point out that most active managers (as they define them) trail the indexes and few are persistent stars. However, the second camp has generally, at least in the academic community, been acknowledged as having been successful.

Take trend-following or momentum investing. In the last 20 years, academic studies have piled high supporting two propositions over various periods of up to hundreds of years. First, they’ve shown that asset-class index returns that are trending upward tend to persist in moving in that direction. Second, the studies have established that all major drawdowns occur after a trend has reversed and turned negative.

The results have been conclusive. Momentum investing can beat buy-and-hold investing. Nobel Laureate Eugene Fama and researcher Kenneth French found in their study of factors (inconveniently, I believe) that the primary factor contributing to returns in the long run was momentum.

And the reason for this outperformance was not because trend following outperforms in an up market. It doesn’t. Rather, it is because momentum investing misses the major part of the really big drawdown events that occur in the middle of the business cycle.

Differences between “strategic” and “tactical”

A similar argument of semantics in finance revolves around the words “strategic” and “tactical.”

The plain meaning of each should allow for no misunderstanding. Yet the industry persists in confusing the two. We hear regular claims using the contradictory phrases of “active strategic allocation” and “restrained tactical investing.”

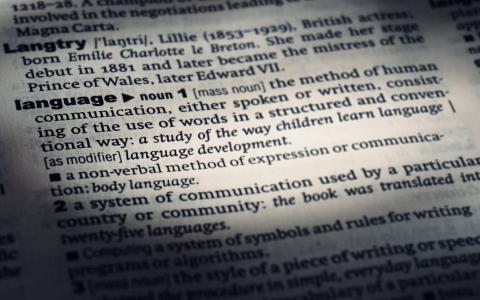

According to the dictionary, “strategic” means “the identification of long-term or overall aims and interests and the means of achieving them,” while “tactical” denotes “methods used to achieve a particular result.” On one level, “strategic” suggests planning, and “tactical” involves action.

I like to think of the difference between the two in baseball terms. Strategic is a plan to “cover all of the bases.” Tactical is “being at the right place at the right time.”

The manager can place his fielders in the spot where the ball is likely to be hit. Yes, he may wave them a little to the left or the right or deeper or shallower, but, essentially, “being strategic” is positioning before the action takes place.

However, after the pitcher throws the ball, tactical takes over. By a prearranged plan, a ball hit on the ground causes the first baseman to move to cover first. The shortstop fields the ball, and, in a dance choreographed and practiced in advance, he throws it to the second baseman now covering second, who whirls in one motion to throw the batter out at first. All were in the right place at the right time.

So it is in investing. Strategic allocation is not active investing. It is the placement of dollars into different asset categories that are believed to “cover all of the bases” of future market developments.

In contrast, tactical investing endeavors to be in the right asset class at the right time. Since various financial asset classes dominate at different times, tactical investing is a plan of action that requires moving from one asset class to another. Thus, it is very different from strategic asset allocation, where there is always a presence in each of the asset classes regardless of which are advancing.

Tactical investing can be as simple as a market-timing approach that stays in stocks as long as the trend is up and then moves into a defensive asset class such as bonds or money markets when the trend reverses.

Or, it can be more complicated, following a rotational scheme where the investor seeks to always be invested in the asset classes that are advancing while avoiding those that are lagging.

Should strategies be strategic and tactical?

All of our firm’s strategies have a tactical component, which allows us to deliver on the two parts of being a dynamic risk manager:

1. Managing “dynamically” means not being tied to a calendar when it comes to trading. We can be responsive to the markets. We can change our whole approach to trading on a dime because the applicable economic regime has changed, or the market technicals have weakened. We eschew the “buy-and-hope” approach.

2. In addition to being dynamic, we are also “risk managers.” In contrast with traditional mutual funds, and certainly passive indexers, our first instinct is to control risk. In contrast to both an active manager and a passive indexer, a risk manager should provide at least two services. First, each strategy or portfolio should be tailored to the risk profile of its investor. Second, the manager should employ risk-management techniques in trading the strategy or portfolio.

Remember, strategies are always strategic, but not all of them can say that they are tactical. That is a critical distinction.