(Flexible Plan) It was the fall of 1956. Action from the World Series blared from the radio. It was the New York Yankees versus the Brooklyn Dodgers, game five. Don Larsen threw his 97th pitch. “Strike!” called the umpire, and the audience witnessed perfection. Twenty-seven batters up, 27 retired—all without a hit, walk, or error. The perfect game.

Much was made in the press of the event. I can still see the front-page photo of an exuberant Yogi Berra being held in the arms of a smiling Don Larsen, just off the pitcher’s mound. They have certainly maintained a permanent spot in my memory and probably influenced me and many of my contemporaries to seek this elusive thing called “perfection”: the perfect education, the perfect job, the perfect spouse, the perfect children, the perfect home, the perfect bank account—the perfect life.

In the years since, I think most of us have learned more about perfection. We know that humans can’t attain it (as St. Jerome said, “True perfection is to be found only in heaven”). Larsen didn’t get his 27 outs on 27 pitches. It took 97.

The fallacy of the “Perfect Timer”

Once a quarter, at statement time, most investors look at returns and judge their investment experience. I always wonder what standard they use in making that judgment. Having run an investment advisory business for more than 40 years, I’ve heard lots of “judgments.” The one I have the most difficulty with is the standard of the client who I call the “Perfect Timer.”

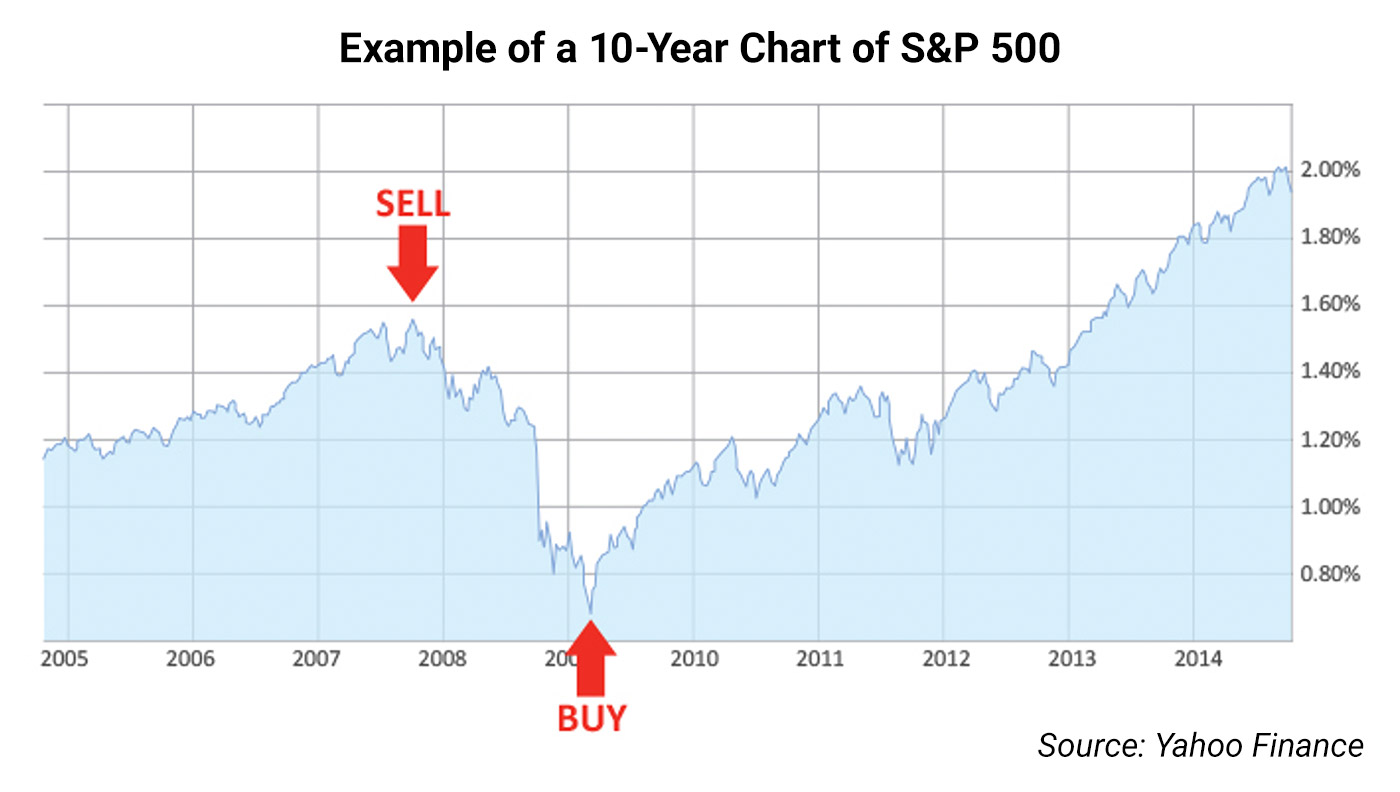

The Perfect Timer believes that active investment is about selling at the “top” and then buying back in at the “bottom,” then repeating the process as often as possible. If you don’t sell at the top, they say, you’ve lost them money.

Of course, there are many problems with this approach. First, no one can pinpoint tops and bottoms consistently for any reasonable period—including the Perfect Timer. “Tops” and “bottoms” can only really be identified in hindsight. And even the exercise of hindsight is dependent on what period you’re examining. Secondly, did the Perfect Timer indicate that they wanted to buy when that bottom was hit or sell on the date of that top? Not likely. So why do they talk about “losses” from some unattainable goal that they were not prepared to act upon?

The line of a stock market chart is not smooth—it’s jagged. When you look at any 10-year chart, the major highs and lows jump out at you. They are so obvious.

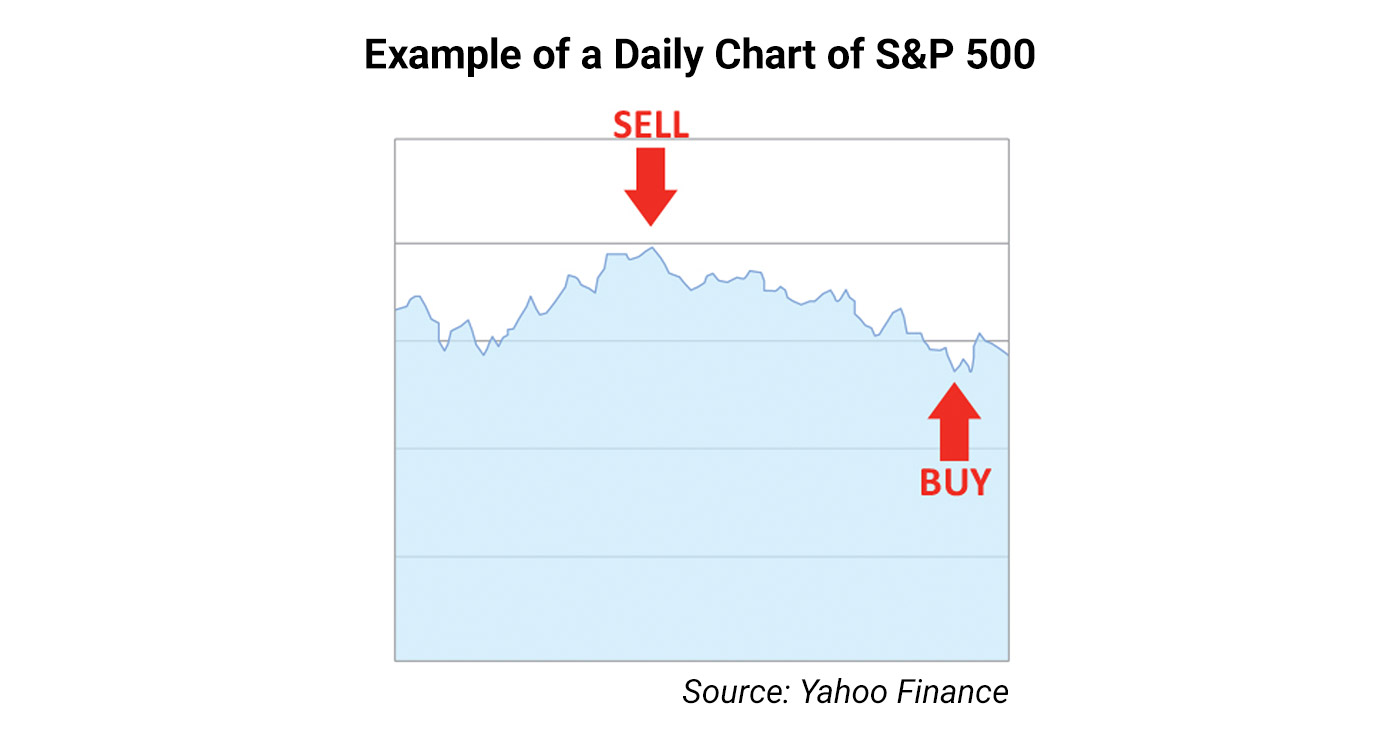

But the highs and lows are also obvious in hindsight when you zoom in at the one-year, quarterly, monthly, weekly, or even daily view. At each level, it is easy to imagine getting out at the top and buying in at a low during the ever-shorter life of the chart.

The sad fact is that none of these trades is consistently obtainable except with perfect hindsight. I love the ad that shows a couple asking a bank teller for a pair of “hindsight glasses.” The teller informs them that they have been discontinued. The fact is they never existed. As Salvador Dalí wrote, “Have no fear of perfection—you’ll never reach it!”

The chart does, however, focus our attention on the fact that, in evaluating performance, the period is important. And this is also a big part of what we consider perfection. Often when we say something is “perfect,” what we mean is “in that moment.” It’s only “perfect” in that snapshot clipped from the long-running movie that is our life.

Technology provides us with examples of this. We get the latest Apple iPhone. It’s the “perfect” phone, we say. Two years later, we must have the newest version of the Apple iPhone—it’s now “perfect.” Time changes. Even what’s “perfect” changes.

Clients invest for a purpose—to meet their long-term goals

Most invest not for the moment but for a purpose. They are looking to fund a future “liability,” be it a home, a child’s future education, or their own retirement. Obviously, these long-term goals have nothing to do with the highs and lows of a stock index on a daily chart. Nor are the weekly, monthly, or even quarterly charts very relevant to deciding if we are meeting our investment goals.

Financial behaviorists have concluded that most people should not look at their returns more often than once a year. Why? Because experience has shown that there are two major impediments to successful investing: 1. Overconfidence at market tops causes some investors to overcommit to risky investments. 2. Conversely, their overwhelming pessimism at market bottoms can lead to abandonment, usually at a very inopportune time.

So why do we send out quarterly statements? We have no choice, even though we know that by doing so we increase the chances of our clients making a wrong decision based on results that are too short term to properly evaluate performance toward their goals. This is just one more example of where the law and science are not really in sync.

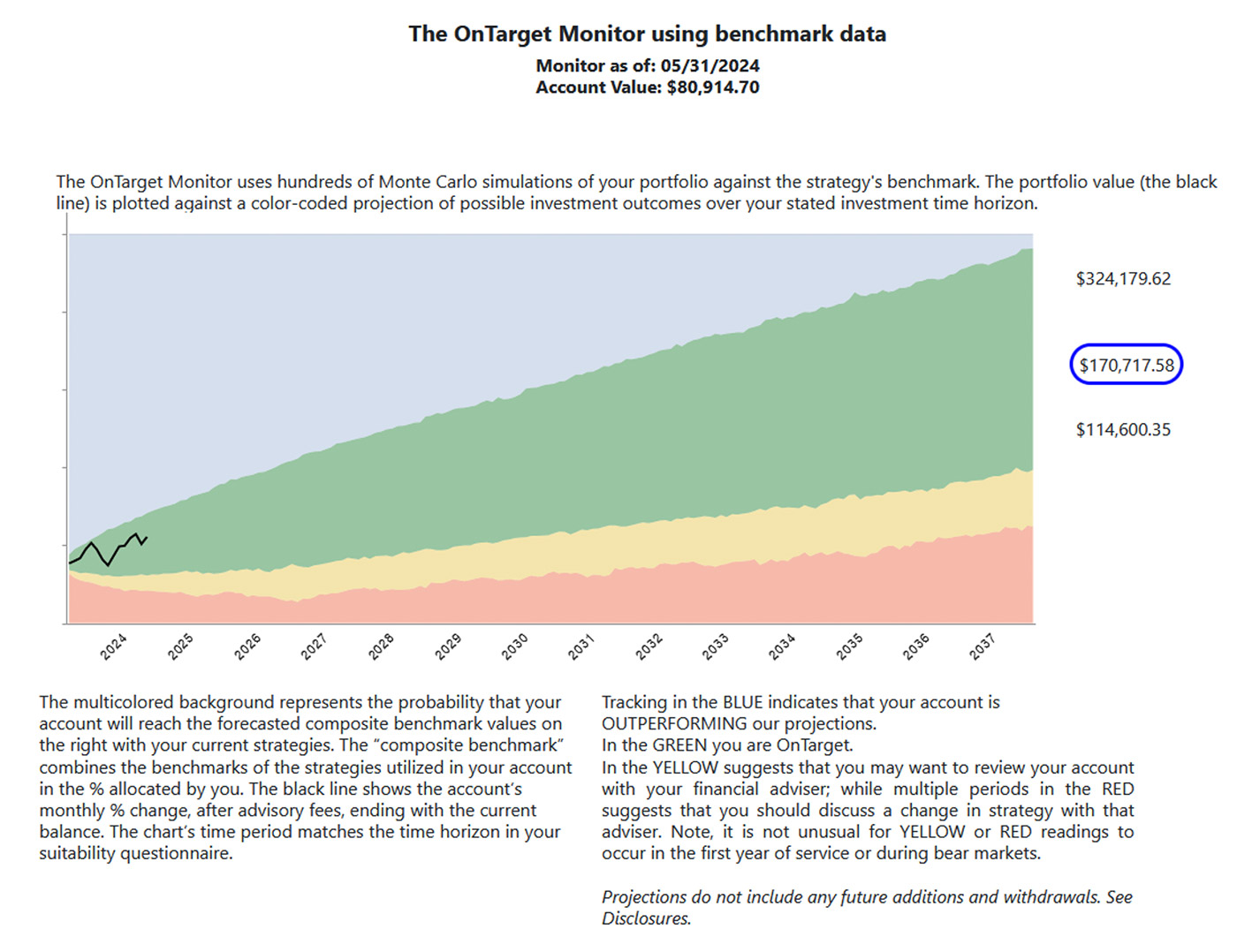

At our firm, we seek to minimize this tendency to focus on short-term results (technically called “narrow framing”) by providing a long-term chart called our OnTarget Monitor. It puts performance in a long-term perspective based on an established goal and the likely performance of the mix of strategies chosen by each client.

Source: Flexible Plan Investments. See disclosures.

The OnTarget Monitor does not put this perspective in exact or “perfect” terms but rather provides ranges of probabilities of performance. If performance is in the blue zone, the portfolio is outperforming expectations. The green zone is normal performance, and the yellow and red zones are areas of increasing divergence from expectations. A bear market can throw even the best strategies or diversified portfolios briefly into the yellow or red zones. However, prolonged duration in the red zone calls for a discussion between the client and financial adviser to consider a different combination of strategies.

By quantifying expectations and displaying them graphically, we seek to focus our clients on a standard of performance that matches their goals and stated suitability profile. (A client’s suitability profile is extremely important in judging performance. Since all of the profiles target less long-term risk than the S&P 500, for example, comparing returns to that index is comparing apples and oranges.) This objective standard stands in sharp contrast to what we often call “perfection.”

Forget perfection. Strive for progress.

What is declared “perfect” is often subjective. Your “perfect” sandwich may be completely unappealing to someone else. That’s another reason why focusing on perfection is a problem—the target is not the same for every person, so how can a money manager focus on it?

The word “perfect” comes from the Latin verb “perficio,” which means “to finish.” That is consistent with Aristotle’s definition of “perfect”—a finished thing—something to which nothing can be added or removed to achieve something better.

Unfortunately, Aristotle’s definition of perfection results in what philosopher Giulio Cesare Vanini, hundreds of years later, termed the “perfection paradox.” For something to be perfect, it must also be perfectly adaptable. And if it is adaptable, it is not finished. As such, Vanini said, “Perfection must be imperfect.”

These days you can’t go two minutes without encountering some inspirational quote that reflects this paradox and suggests a solution: “Strive for progress, not perfection.” “Striving for perfection is demoralizing.” Or, as Edwin Bliss said, “The pursuit of excellence is gratifying and healthy; the pursuit of perfection is frustrating, neurotic, and a terrible waste of time.”

I’ve spent almost 50 years seeking the “perfect” strategy, one that generates positive results no matter what period I examine—daily, weekly, or even quarterly. There is no such strategy.

Instead, our firm seeks progress and excellence in the process of attaining it. We have always been committed to dynamic, risk-managed strategies that can change to meet the challenges of evolving market conditions rather than simply buying and holding. Market environments change, and so the strategies that flourish in them also change.

The investment strategies we offer will not yield gains in every quarterly report. But each has been designed to produce the best risk-adjusted returns. It’s not a “perfect” game, but helping our clients progress toward their long-term goals is, after all, what investing is all about.