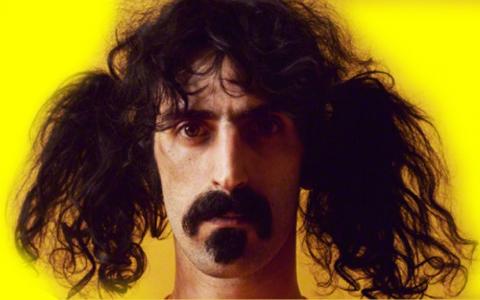

Fight over how to embody the countercultural giant’s notoriously litigious legacy feeds nothing but bad feelings between brothers at an emotionally fragile moment. If you ever needed an example of why independent trustees are critical to dynastic harmony, this is it.

Throughout history, there have only been a handful of guitarists with the legal right to perform under the name of Zappa, and one of them has been dead for decades.

Now there are none. The trustees that oversee the family legacy have pulled the “Zappa” license from brother Dweezil Zappa – Frank’s son -- forcing him to jump through new licensing hoops just to play his dad’s music.

On the surface, it’s a straightforward case of protecting the trademarks from pirates. But since the family already cracked down on other tribute performances, there really aren’t any outsiders left to infringe.

The music is notoriously difficult. Dweezil is one of the few people on the planet who can even attempt some of these arrangements with anything near Frank’s aplomb.

And since Dweezil was actively paying license fees and playing the songs, all the trustees may have bought here is a whole lot of tension and reduced cash flow for the estate they all share.

Either way, while the decisions may ultimately boil down to hard business, the fact that it’s all being conducted within the family doesn’t help. It’s too bad the Zappas don’t have an independent trustee to mediate on the behalf of all the stakeholders.

Who are the brand police?

Zappa was always more of an underground sensation than a breakout commercial success. His “big band” approach ensured that touring would lose money, so he recorded 66 albums across 27 years instead.

Unfortunately, the fan base was loyal but narrow.

They’d buy each album once or twice and maybe pick up some shorts or other memorabilia, but that was really the core source of his estimated $40 million career earnings.

And since the business model relied on a steady stream of new material, his death in 1993 forced some serious strategic decisions.

Frank saw the economics of the music industry shifting late in life and urged his wife Gail to cash out and go.

Instead, she opted to consolidate his legacy, paying litigation fees to round up all the outstanding rights and suing even theoretical competitors into oblivion.

When the family didn’t have the recordings, she pushed the publishing rights in order to chase royalties there. The problem there was that the Zappa catalog is pretty distinctive.

If you’re not playing it more or less like Frank and the Mothers of Invention would have done it, there’s not a whole lot of point.

Copy the original too closely, and Gail sued for infringement.

Either way, once the Zappa name was locked up in active trademarks, the cover bands had a hard time marketing themselves and making money for anyone.

Dweezil got by over the last decade because his mother let him perform under the “Zappa Plays Zappa” trademark under license.

Supposedly he paid a healthy fee in order to do so, but because he was one of the beneficiaries of the family business, he got a piece of that money back.

However, Gail died last year, passing on control of the Zappa Family Trust to two of her four children who promptly pulled the license from their brother. He’s mad. And he’s effectively called their bluff.

Don’t eat the golden eggs

A dead artist’s estate isn’t only in it for the money, so to speak: it also exists to protect the creative legacy.

Sometimes these priorities intersect. Sometimes they conflict, making the executors lean in one direction or the other.

Looking at the decades Gail ran the estate, it’s fairly clear that she leaned on the side of protecting the legacy.

The story of the Zappa Family Trust is one of building barriers to keep other people from making a penny on Frank’s genius. That’s the family’s right.

But if they want to make money, throttling the people who are still trying to commercialize the songs is not often the best way to do it. Gail kept Frank’s music off iTunes for years.

Arguably Dweezil was the biggest “brand ambassador” the family had, and he was not exactly a stadium act. “Zappa Plays Zappa” played a lot of shows, averaging 50-60 dates a year recently.

They sold t-shirts, posters, the works. They kept the Zappa cult relevant, vibrant and alive.

And they kept the revenue flowing.

Maybe the trustees simply don’t want that. If so, it’s unfortunate because their job is to manage the trust assets to the maximum financial benefit of all the beneficiaries.

Unless they have better options on the line when it comes to live performance, pulling the plug on a money-making venture doesn’t really seem to be the way to do that.

And there were other ways to manage Dweezil’s participation in the family business.

If he’s simply trading on the family name, he pays the licensing fees just like any other cover band.

Those fees go on to enrich all the children and he gets to keep playing.

However, if the licensing fees rise beyond his desire to pay, the family can shut him down.

He’s unhappy because he doesn’t get to play Frank’s music any more and the revenue dries up for everyone. I’m not convinced there’s a whole lot of money at stake here either way.

It looks more like the trust lawyers trying to establish a precedent and applying it without favoritism – even if your name really is “Zappa,” you can’t squat on the trademarks.

The problem here is that Dweezil can’t legally be alienated from his own last name because his relatives own the marks.

He can promote gigs as “Dweezil Zappa,” pay no licensing fees and the fans will figure it out.

That’s apparently what’s happening this summer. He can play the songs. There’s not a huge amount of money in it, but it keeps the brand active on the performance circuit and the music alive.

The trust now has to sue or keep quiet. Since he’s their brother, it’s a fraught decision. And since he’s the Zappa child who gets in front of the fans, a lawsuit can generate unfavorable publicity on that side.

Maybe there’s a little sibling rivalry involved.

If so, an independent trustee might have handled things differently to get the best outcome for all the kids collectively. But it’s too late for that.