In the league of elite investors, few can rival the late David Swensen, former head of the Yale Endowment. As Chief Investment Officer of this multi-billion dollar fund, he delivered top performance over multiple decades, and his investing style influenced an entire industry. Swensen’s innovative and rigorous approach to asset allocation and expanding its range was revered, with others rushing to replicate it. This approach became known as the “Yale Model”, and revolutionized endowment investing.

Over the span of three decades Swensen took the Yale Endowment from $1.3 billion to over $30 billion, averaging over 12% annual returns along the way. His investment principles were built on the power of diversification to mitigate risk, something he became enchanted with when he first studied under James Tobin, the Nobel Prize winning economist.

So, what lessons can we learn from the legendary investor?

The Power of Long Term Views

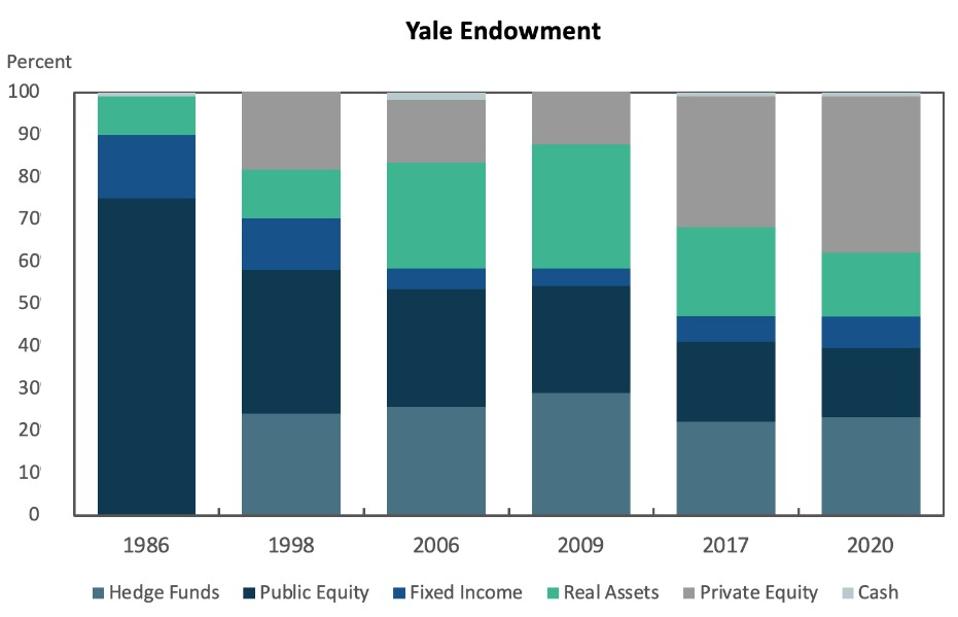

From the onset, Swensen understood that an endowment’s long life significantly enhanced its ability to search for yield beyond public markets. By eliminating the constraints of a reactive, short-term approach, Swensen delved into private assets, which afford greater access to management, and insight into their strategies as well as value drivers. He realized that private assets that required rigorous research and have no active exchange, offered a premium to patient investors that could forgo the need for immediate liquidity. When he started at Yale, the endowment had 75% of its investments in public equities. Seeing higher yields in alternative assets such as private equity, hedge funds, real estate and natural resources – he aggressively shifted the asset mix.

Superior results followed and his track record outpaced peers. Today, public equities are only 16% of Yale’s portfolio with the bulk of its holdings in private equity, hedge funds and real assets.

Yale endowment

SLC MANAGEMENTWhy This Approach Works

Swensen believed every investor has three tools: asset allocation, security selection and market timing. To him, the most critical driver was asset allocation, and the discipline to stick to an optimal asset mix was key to achieving long-term goals.

However, if left unattended, any portfolio asset mix drifts over time. If certain asset classes significantly outperform others, they will dominate the mix. Similarly as assets underperform, they lose prominence.

Accommodating these drifts requires periodic rebalancing to restore the long-term mix, which in turn requires selling some winners and buying some laggards. This all seems counterintuitive, but the essential thesis behind periodic rebalancing is that when major asset classes rise or fall more disproportionally than others, it becomes more likely they will start to revert to their long term average rather than continue to over or under shoot.

Therefore, rebalancing helps capture these price dislocations, which should improve portfolio performance over the long-term. Essentially, it encapsulates the advice to “buy low, sell high”. While there are no guarantees, Swensen stood behind this disciplined approach and was confident it could deliver value over time.

Contrarian Investment Decisions Challenge Stakeholders

Portfolio rebalancing is a contrarian strategy. In particular, when the world appears to be falling apart and markets are getting battered, it takes grit to step in and buy what’s on sale, even at deep discounts.

The nerve of even sophisticated investors and their investment teams get tested when markets implode. Swensen’s first test came in October 1987, when he was only two years into the Yale job. The U.S. stock market crashed, dropping more than 20% in a single day.

During fire sales like this, investors should be giddy to snap up bargains. However, significant market drops are terrifying and many investors become paralyzed, rushing to cash out. While Swensen rebalanced by loading up on discounted stocks, his investment committee grew queasy.

Though he was following the approved investment mandate, the committee worried about the firestorm of criticism he would face if he got it wrong and ended up in a prolonged downturn. Eventually Yale’s President weighed in and Swensen prevailed. His swift action delivered significant value as the market rebounded and ignited a long bull run.

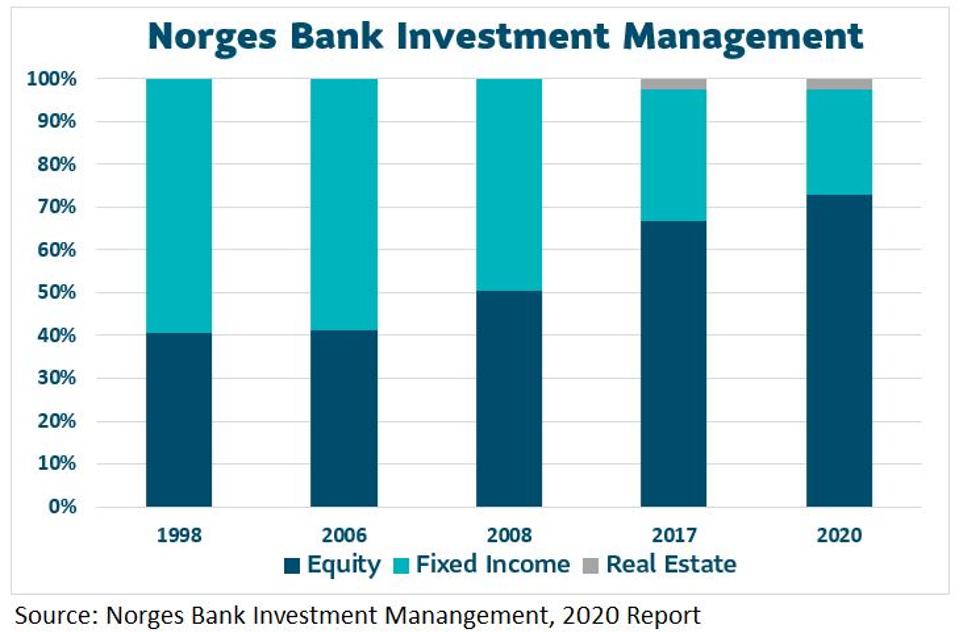

Indeed, Yale’s fearful soul searching is natural in deep downturns. For example, Norges Bank Investment Management, the world’s largest sovereign wealth fund that manages Norway’s oil revenues, paralleled the same scene in 2008.

Back then, its investment head Yngve Slyngstad, had just taken over as the great financial crisis hit and global stocks were getting hammered. Slyngstad called for rebalancing to take advantage of the deep selloff.

As fear griped his oversight committee, the finance minister finally stepped in and supported the move to buy the equivalent of 0.5% of the total global equity market. As with Yale, this set up the fund for a long bull market. Today, Norges is one of the largest holders of equities in the world.

Norges Bank Investment Management

SLC MANAGEMENTAdopting the Yale Model

All in all, the critical lesson in Swensen’s approach is that having a well laid out rebalancing plan is the best preparation for marshalling the courage to act, particularly when terrified. The push to restore asset mix targets as prices drop will help ease some of the paralysis that will naturally grip most investors.

Markets can turn quickly, so it’s easy to be caught off guard absent a plan. As Jeremy Grantham, another investment icon, once wrote: “Be aware that the market does not turn when it sees light at the end of the tunnel. It turns when all looks black, but just a subtle shade less black than the day before.”

Swensen and team understood this and crafted a process and philosophy that drove timely decisions, even when markets were at their worst but value was at its best.

This article originally appeared on Forbes.