(Dividend.com) - Rising inflation caught many economists and central bankers off-guard, prompting the Federal Reserve to hike interest rates and put the brakes on spending, hiring, and economic growth. But, with supply-driven inflation out of the central bank’s control, some investors fear a combination of below-average growth, above-average inflation, and high unemployment.

What Would Cause Stagflation?

Stagflation usually arises from central banks attempting to control inflation when there are factors out of its control. In the 1970s, the Vietnam War and Great Society spending programs caused the federal deficit to soar, while the Arab Oil Embargo tripled oil prices by the decade’s end. Fed Chairman Volkner had to raise the fed funds rate to 19% before calming inflation, causing a pair of severe recessions and a long period of stagflation.

Many investors see parallels to today’s environment. While the federal deficit is lower than it has been since 2019, thanks to strong economic growth, crude oil prices are at multi-year highs and supply chain disruptions are creating inflationary pressure. Many of these factors are outside of the Federal Reserve’s control. And like the 1970s, the central bank was caught off-guard by a sudden spike in inflation, putting it behind the curve in its fight.

The Federal Reserve has a tricky path to navigate over the coming months. On one hand, it must raise interest rates enough to squash demand-driven inflation and achieve a soft landing. On the other hand, it has little power over supply-driven inflation, and raising interest rates too far could cause a recession. The latter scenario could spark stagflation if inflationary pressures remain despite a slowdown in the economy.

The Odds of Stagflation in the U.S.

The good news is that stagflation is far from a guarantee. Since economic growth remains relatively strong, rising interest rates could simply moderate growth rather than spark a recession. Secondly, there are signs that supply-driven inflation could be moderating in some parts of the economy, such as used cars. And finally, rising bond yields and a strong dollar are already tightening lending without the need to raise interest rates.

On the other hand, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine could continue to disrupt energy and food prices. Despite the Biden administration’s efforts to boost oil output, the tight market could translate to high prices over an extended period. Meanwhile, China’s COVID-19 lockdowns and the tight domestic labor market could continue to disrupt supply chains and cause shortages in critical areas over the coming months.

The Federal Reserve has little control over these external factors, such as the price of crude oil. While the U.S. is more insulated than Europe (which is more reliant on Russian natural gas), it could still fall into the stagflation trap if it raises interest rates too fast as supply-driven inflation rises, although the odds are still slim at this stage.

How to Prepare Your Portfolio

Stagflation has a unique impact on investment portfolios. While equities are among the best asset classes during good times, they tend to suffer the most during stagflation. Companies face a brutal combination of rising costs and falling revenue during these time periods, hurting both top- and bottom-line results and sending earnings multiples lower.

Of course, fixed income securities and bond prices tend to suffer nearly as much. Higher interest rates lead to higher yields and lower prices, which is particularly devastating to those invested in long-term bonds. That said, bonds could offer better performance than equities, particularly if interest rate increases are already priced into the market.

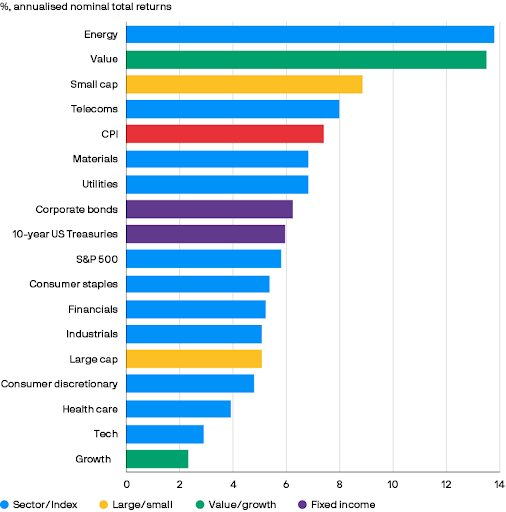

Using the 1970s as a data source, JPMorgan analysts found that energy and value stocks outperformed during stagflation, as shown above. In addition, small-cap, telecom, materials, and utility stocks did rather well. And, not surprisingly, growth and tech stocks were among the worst performers, although today’s tech stocks differ from those in the 1970s and 1980s.

The Bottom Line

Rising inflation has sparked fears of stagflation. Since today’s circumstances differ from the 1970s, these risks remain relatively low at the moment. That said, the risk of supply-driven inflation remains elevated and could spark a crisis if the Federal Reserve raises interest rates too much and sends the economy into a recession.