(Morningstar Managed Portfolios) The range of economic outcomes is particularly wide these days.

A quick review: Inflation remains persistently high, and the Federal Reserve’s response—while arguably delayed—is perhaps more hawkish than some expected. The 50-basis-point hike in May, for example, was the first of its kind in two decades, and it was followed by two 75-basis-point hikes in June and July, which we hadn’t seen in 28 years. At the Fed’s yearly gathering in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, this past August, Fed Chairman Jerome Powell suggested more of the same to come, saying the Fed planned to “keep at it” until the “job was done.” In this case, the job is restoring price stability, bringing inflation down to lower levels.

Whether the Fed is going to have the impact it would like to have is debatable, considering that at least some of the inflation is coming from the supply side (consider supply chain disruptions, for example, and the Russia-Ukraine War), as opposed to the demand side. It also comes on the heels of a remarkably accommodative policy stance, and rates today remain at low levels on an absolute basis. Nevertheless, the economic impact of the rate hikes—and the overarching inflationary environment—is real. The booming housing market has shown signs of slowing, for example, while consumer confidence has declined, and we’ve seen layoffs at various companies—particularly within technology.

The combination of high inflation and economic weakness has conjured up the specter of stagflation, a particularly dreaded economic environment of high prices, and low growth that weighs on corporations and individuals alike.

We'd caution that stagflation isn't exactly a done deal, even in today's climate. For one, inflation is often its own cure. And as it relates to today's conditions, we already see signs that prior sources of inflation are easing, such as supply chains. Second, despite the challenges, the U.S. economy entered 2022 with good underlying conditions, putting it in a strong position if a severe recession were to come.

With those factors in mind, it's well within the realm of possibility that we see inflation ease in the coming months, while economic growth rebounds. Of course, the market would also spot the brightening conditions long before they show up in economic numbers, rewarding investors for staying the course during today's uncertainty.

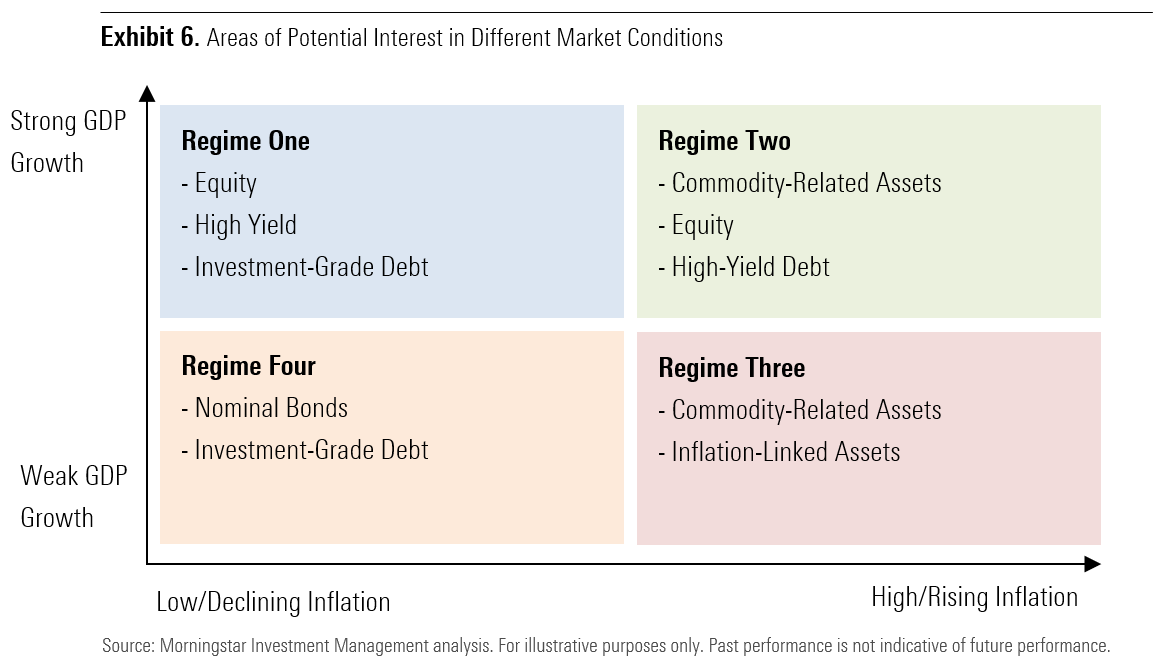

Unfortunately, like everyone else (even the economists among us!), we lack a crystal ball to tell us exactly how economic conditions evolve. As investors, we also have the added complexity of how each economic environment will impact different asset choices. As a result, we must plan for a myriad of environments. For an economic recovery, that's a fairly straightforward analysis, but for a stagflationary environment, we must look through the lens of history.

The most prominent period of stagflation in the U.S.? The late 1960s and early 1970s, when monetary policy collided with oil supply shocks, currency depreciation, unanchored inflation expectations, and climbing wages. Over that stretch, both U.S. equities and U.S. fixed income broadly suffered, though there were pockets of resilience, such as commodities and gold.

However, even within equities and fixed income, there were varying levels of defensiveness in a stagflationary environment. To understand what could hold up and what might struggle in today's environment, we walk through the fundamentals of both asset classes below, wrapping up our thoughts with a review of current positioning.

Equities—Thinking It Through

When considering the potential impact of a stagflationary regime on equities, we think it’s instructive to work through the fundamental drivers of returns. Slower economic growth has the effect of reducing revenue potential. If we break this down further, the sources of revenue growth can be split into unit (volume) growth and pricing, where reduced economic growth has the effect of tamping down volume growth as well as muting pricing power. With that said, an inflationary backdrop provides more cover for companies to “pass through” higher input costs via higher prices.

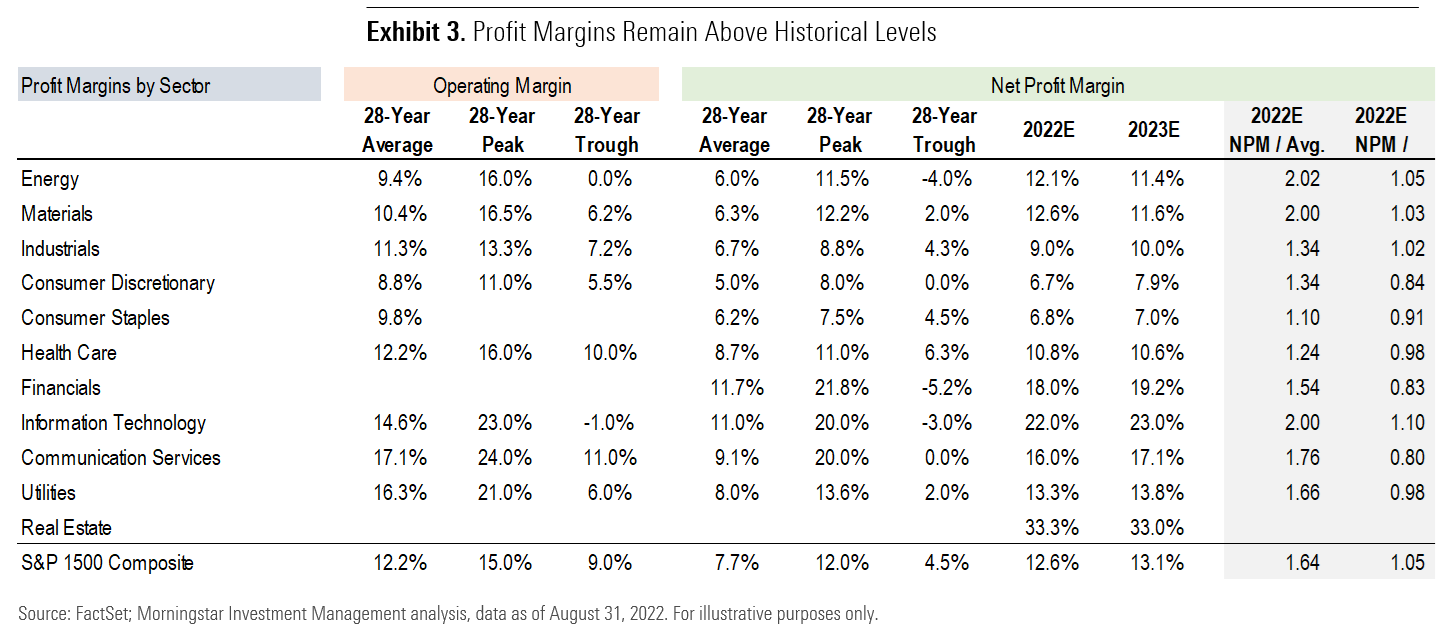

This tug of war between input costs and the ability to pass through price increases reveals itself in profitability. From a profit margin perspective, sectors that would appear to be “over-earning” versus historical average levels include energy, materials, and information technology. Given the strength in energy and other commodity prices, it's not surprising that profit margins in those sectors are higher than history—and, to the extent that high commodity prices continue amid capital discipline by these companies, it would not be surprising for these margins to continue to exhibit strength relative to historical levels. On the flip side, margins within information technology could potentially be vulnerable, particularly to the extent that wages accelerate.

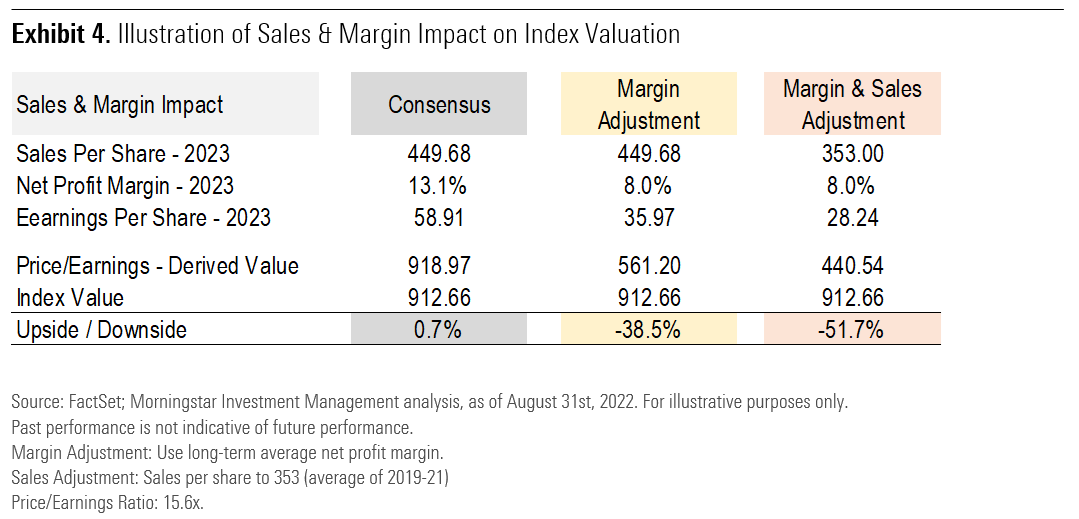

The aggregate effect of sales and margins on index valuation can be profound. In the case when aggregate margins revert to longer-term historical average levels, we'd see a reduction of nearly 40% for earnings per share—and valuations—assuming no change to the price-to-earnings multiple. Reversion of sales-per-share toward recently achieved levels could render a further 13% impairment to index valuation levels—again, holding P/E levels steady. This analysis is not intended as a definitive prediction of such a scenario unfolding, but rather, it's part of a series of cases that we model in our process of understanding varying economic regimes.

Valuation Considerations

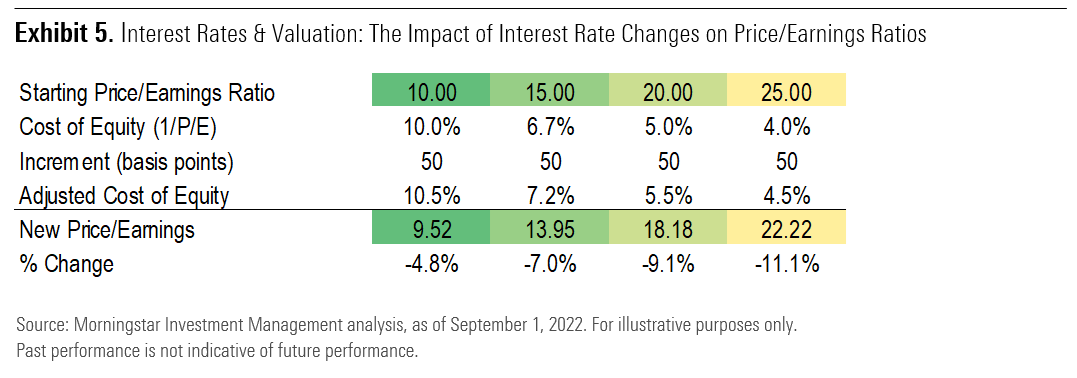

One of the more notable features of an inflationary regime is the policy response, which seeks to offset inflation through increased “policy” interest rates. This, in turn, manifests itself into rising the so-called “risk-free rate” via Treasury yields. The risk-free rate is an important building block in thinking through the cost of equity capital (the return required on an equity investment) in models such as the capital asset pricing model.

Not every single basis point of directional change in the risk-free rate necessarily “sticks” in terms of an embedded, permanent increase in the cost of equity capital. To deal with this, we find it a helpful exercise to highlight the impact of increasing risk-free rates on the cost of equity capital, looking at it from various “starting points” of price-to-earnings multiples. The higher the starting P/E multiple, the lower the implied cost of equity.

Looking at the sensitivities, the higher the starting P/E multiple, the more sensitive the valuation is to changes in the risk-free rate. In our example below, when you use a starting multiple of 25, increasing the cost of equity by 50 basis points reduces the imputed multiple by 11%—whereas with a starting P/E of 10, the impact of increasing the cost of equity by 50 basis points reduces the imputed multiply by less than 5%.

The above analysis does not take the equity risk premium into account. On balance, with the challenging backdrop presented by a stagflationary regime (slower growth, cost and margin pressures, and higher interest rates), it’s likely that equity risk premia could also rise, serving to further dampen P/E multiples.

It’s this perspective that causes many investors to wonder if the high-priced areas of the market, such as technology and consumer discretionary sectors, could be particularly vulnerable to continued rate increases.

Sector & Country Implications

Given the potential for a stagflationary backdrop, there are certain sectors that arguably would be better positioned to withstand such a challenging environment. Commodity-facing sectors, such as energy and materials, may not outright thrive in this backdrop. But by continuing the capital discipline and cash deployment, they are potential relative winners.

On the other hand, higher-growth, longer-duration, higher-multiple sectors, such as technology, could be challenged. Here, we’re not making the case that revenue won’t grow or that these companies don’t possess pricing power. However, a slowing economy would have the effect of dimming revenue growth prospects for the vast majority of companies. As part of this, it’s probably not realistic to assume that tech companies, particularly those whose revenues are driven by enterprise capital spending by businesses, would be completely immune. Therefore, expected growth levels may not be met, which could be a problem given high expectations for growth, even after a difficult first half of the year. A potentially compounding factor could also be the comparatively lofty starting multiples accorded to this sector.

Elsewhere, lower growth, highly regulated “bond proxies,” such as utilities, could also suffer on a comparative basis. The same may apply to consumer stocks, where a shift in spending toward essential items could drive incrementally improving results (at least relatively) for staples companies versus discretionary companies.

There are certain sectors—such as financials—where revenues and profits are not directly a function of the broader economic conditions but are connected to the interest rate and credit backdrop. A stagflationary regime would present complexity in this regard—notably, the level and trajectory of interest rates, the shape of the yield curve, and the dynamics of the credit cycle.

The extent to which rising interest rates would help or harm bank earnings depends, in part, on returns accruing to their cash and other invested assets relative to the funding costs associated with their deposit base. The shape of the yield curve also has an impact—a steeper curve trajectory would potentially allow for stronger earnings power, whereas a flat or inverted curve could serve at the margin to impair earnings. Finally, the credit cycle and how it’s impacted by the economic backdrop is another crucial element to bank earnings.

From a country perspective, Brazil leaps to mind as a potential relative winner. It’s not without risk, especially as its election cycle unfolds—but the Brazil index does contain a high number of commodity-facing companies, while its policy rates have already risen substantially. As a potential kicker, its currency also appears undervalued, which could prove a tailwind. According to our calculations, where we estimate the "valuation-implied return," we'd expect yearly returns in the vicinity of 8.9%, which is attractively valued both on an absolute and relative basis.

Another country with an attractive valuation-implied return is Germany, although it's potentially subject to revenue and cost pressures associated with a stagflationary backdrop. Germany's energy sourcing problems are well-known, and its valuation reflects this concern, at least in part. However, we’re most concerned with longer-run effects of lower growth and inflationary pressures that could decrease that expected return stream beyond the short run.

Potential Offsets

Just as we think it’s instructive to consider a stagflationary regime in thinking through portfolio construction, it’s also important to consider alternate scenarios. For instance, what happens if a stagflationary environment is resolved or dissipates? In this case, presumably growth would revert higher and inflation levels would revert lower. Correspondingly, the policy imperative toward higher interest rates would reverse course.

A resolution of stagflation would likely, therefore, yield improved revenue and profit growth prospects, as well as improve valuations in the form of a lower cost of equity (resulting in higher P/Es). This would seem to argue in favor of broader equity exposure, as well as a tilt toward growth-focused, longer-duration, higher-valuation sectors such as technology stocks. And, “bond proxies,” such as utilities and REITs, which would tend to benefit from falling interest rates, could also do well in such an environment.

The Fixed Income Side of Things

One of the greatest utilities of fixed income, of course, is the diversification that it can offer relative to equities. That is, when stocks slide, investors look to fixed income to offset or at least minimize the losses. But recently, fixed income has struggled to live up to those expectations—the straightforward 60/40 stock/bond portfolio (as defined by 60% in the S&P 500 and 40% in the Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate Bond Index) has lost 13.9% since the beginning of the year through August. Driving this result, the S&P 500 has lost over 16% and the Aggregate Bond Index has lost close to 11%.

A stagflationary environment could extend, rather than reverse, that trend. Both growth and inflationary dynamics have direct impacts on fixed-income prices, and it's the balance of those effects that impacts returns in different macroeconomic environments.

High inflation tends to negatively impact fixed-income returns, especially if it's met with aggressive monetary policy. Low growth, on the other hand, tends to be a tailwind for high-quality bonds as investors seek safety. In addition to the central bank’s policy stance (“don’t fight the fed”), drivers of fixed income returns depend both on the sector in question and market expectations.

The behavior of nominal Treasury bonds—the asset many of us think of as a safe haven—can be particularly sensitive to which narrative (economic activity or inflation) is driving asset prices.

When it comes to the combination of low growth and high inflation, the actions and words of the Federal Reserve can become the main catalysts for price movements in the short term. Historically, when the Fed aggressively acts to tame inflation, nominal Treasuries underperform. Furthermore, if inflation remains sticky, Chairman Powell has stated that the Fed is willing to continually increase interest rates and go through "a sustained period of below-trend growth." That could be bad news for U.S. Treasury bonds.

On a positive note, though, prices have already moved a lot from where they were at the start of the year, with the market reacting to the Fed’s tightening. Therefore, investors are being paid significantly more than they were to take on interest-rate risk. Yet even given the moves since Jackson Hole in August, Treasury prices could continue to fall if inflation continues to prove stickier than the market is pricing in.

That said, the current fragility of the U.S. economy should be noted. This is important as U.S. Treasuries are arguably among the best safe haven assets during a typical deflationary recession. The tug-of-war on Treasury prices between inflation and recession risk is difficult to predict, yet as Treasury prices fall, protection for investor portfolios becomes cheaper to obtain.

Investing Outside Treasuries

When it comes to Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (TIPS), the market’s expectations for inflation changes tend to drive returns (especially relative to nominal Treasuries). Therefore, these bonds can act very differently in periods of low growth and high inflation.

In previous periods of stagflation, TIPS have been one of the best assets to hold. Earlier this year, TIPS breakevens spiked as investors weighed the consequences of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Now, the market’s pricing of inflation expectations is largely back to where it was to start the year and, therefore, not necessarily pricing in a sustained period of high inflation. This means that there is potential upside in TIPS, if inflation remains elevated and the market readjusts its expectations of future inflation.

As we move up the risk curve to corporate credit, we need to consider both the impact of interest-rate changes as well as credit spreads (the increased yield over treasuries that the market demands to take on the additional risks). Interest-rate risk is similar to Treasuries, where we'll see a negative impact when the Federal Reserve is focused on fighting inflation.

This is less concerning for high-yield bonds, as they tend to have less interest-rate risk; however, investment-grade corporate bonds carry longer maturity dates and meaningful duration risk. Combining the inflationary impacts with low economic activity increases the potential for credit spreads to widen leading to additional price losses for corporate credit.

We note that the ideal environment for corporate bonds is typically high growth and low inflation. The scenario we're discussing is the opposite of that, and corporate bonds have been one of the worst performers in previous periods of stagflation.

Looking Beyond the U.S.

If we begin to expand our universe to fixed-income assets outside the U.S., we must consider additional factors. Not only can economic and inflation undercurrents be different in each country, but central bank policy may also diverge from the Federal Reserve. This will have an impact on government bonds and credit spreads, as well as currency exchange rates.

If we find ourselves in a period of sustained global stagflation, regions that are likely to perform relatively well are places where the central bank has already acted aggressively to fight inflation by raising interest rates and have economies that are not as vulnerable to high inflation. In that regard, the commodity exporters (such as Brazil, which we mentioned) are likely better positioned.

The Surprising Utility of Cash

For multi-asset investors, it’s also important to think through the role of cash in a stagflationary environment. Let's start with a powerful observation: Even with the increase in interest rates, cash is highly unlikely to keep up with prolonged high inflation, making it a surefire way to deliver negative "real" returns.

That said, cash can act as a store of nominal value, playing a valuable role in a portfolio if both equities and bonds are losing value. Not only will cash mitigate the absolute level of losses an investor may experience if stocks and fixed income lose value, but it can also act as dry powder, which an investor can then redeploy into the market as asset valuations become cheaper. All else being equal, this improves the long-term returns of a portfolio.

What works in this environment will likely struggle if the narrative shifts to either higher economic growth, lower inflation, or both. While we do not want to build portfolios just for one environment, it's important to ensure robustness as environments shift. As mentioned, nominal Treasuries will likely be a great place to be if we enter a traditional deflationary recession. If the global economy surprises to the upside, riskier assets, such as emerging-markets debt or corporate credit, would also likely perform well.

Pulling It All Together: Multi-Asset Portfolio Management

A stagflationary environment is far from a guarantee, but there’s no question that the risks are higher today than they’ve been in recent years. And as we detailed above, the implications for various asset classes are meaningful.

So, how are we acting? Valuation is the critical variable in our assessment of risks and opportunities, and we’ve kept stagflation in mind as we’ve positioned strategies. In fact, it’s with the potential for stagflation in mind that we’ve slowed our exit from energy positions (including maintaining exposure to master limited partnerships [MLPs] or European energy companies) that we think aren’t overly expensive and may provide a hedge in the event stagflation takes root.

On the fixed income side, we’re growing more interested in TIPS, and, despite improving spreads in corporate and high-yield debt, we’ve been judicious in any increases to the space, noting room for spread widening.

What happens in the event recession risk fades, inflation abates, and rate increases slow? In a return to growth, we believe some of the tech companies that have suffered this year could rotate back to market favor. Given that many of these names are less overvalued than they were previously, we've modestly reduced our underweight to those areas, adding judiciously to the likes of communication services, home to Meta (Facebook) and Google. Similarly, with valuations in the financial sector more attractive than other segments of the equity market, we’re willing to take on a bit of the complicated interest-rate calculus to add exposure there, with the expectation that banks and the like could surprise on the upside.

Rounding out multi-asset positioning is exposure to alternatives and cash, both of which have offered ballast so far in 2022 and, as detailed above, leave room to readjust.

The overarching takeaway here? The macro environment matters. When there's higher risk—as there is today with stagflation—we take it into account as we position portfolios. But given the uncertainty around the future, we can’t plan for just one expectation. Instead, we position for a range of outcomes, with the aim of creating enduring portfolios that help investors worry less—not more—about headlines.