(Morningstar Investment Management) Japan has been one of the most unloved equity markets in the world for decades—it’s been a pariah of sorts.

However, investing is about what happens in the future, not what happened in the past. And many investors are turning a curious eye toward Japan.

The reason? Japan has become an aggressive market reformer—pushing companies to prioritize shareholders—and a welcome change.

For some, these reforms may get overlooked because of recent history.

A Brief History of Investing in Japan

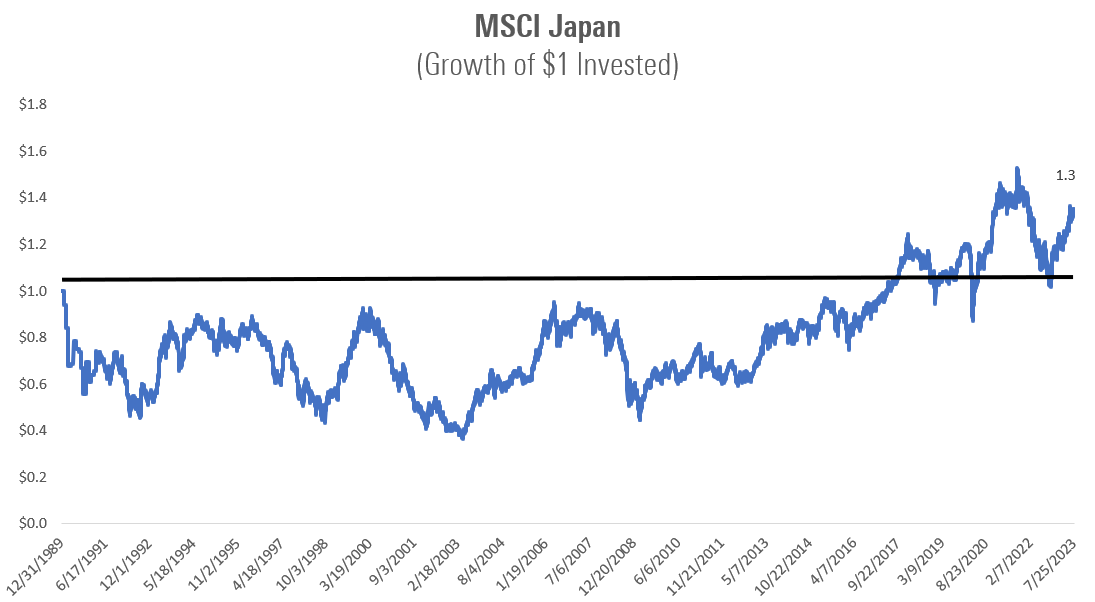

One dollar invested in the MSCI Japan Index in 1990 grew to just $1.30 through the end of July 2023. And that dollar was underwater for nearly 30 years—not inflecting positive until 2017.

Exhibit 1

Source: Morningstar Direct. Data as 7/31/2023. Indexes shown are unmanaged and not available for direct investment.

Meanwhile, $1 invested in the S&P 500—with dividends reinvested—grew to $26 during that period.

It’s easy to take this data—30 years is a significant sample—and harbor the view that it’s a waste of time to invest in Japan.

But low returns over the past few decades were mostly a product of one of the largest asset bubbles in history. Using data from Allegro Japan, the peak of the Japanese asset bubble in the 1980s reads like fiction.

Some of the interesting details include:

- Nine of the top 10 largest banks in the world were Japanese.

- The Greater Tokyo area had a GDP larger than the United Kingdom.

- The Tokyo Imperial Palace—occupying roughly 285 acres—was estimated to have a value greater than all the land in California.

- The Japanese property market was worth approximately four times more than the American property market, despite Japan land mass only comprising roughly 4% of the U.S.

- Golf club memberships became a tradable commodity with a total value estimated at $200 billion.

To the last point, the New York Times ran an article in 1987 titled “Want to Play Golf in Japan? Got a Million”—a story about a country club where membership was capped and the only way a new member could join was if an existing member canceled their membership.

At this exclusive course, nobody was willing to cancel their membership. An offer of more than $3.5 million followed to try an entice a member to turn over their membership.

The offer was declined—it truly was an insane time.

Japanese stocks had spent more than a decade in the ‘70s and ‘80s compounding at 20% annually. Japanese stocks were trading at a CAPE ratio of nearly 100, more than double where U.S. stocks traded at the height of our most famous bubble—the dot-com period in the late ‘90s.

Japan Getting Serious About Change

The real estate and equity collapse that followed was mostly a result of prices that overshot reality.

The decades of severe underperformance that followed forced Japan to get serious about reform. The changes had been coming in bits and pieces, but it has gotten more serious recently.

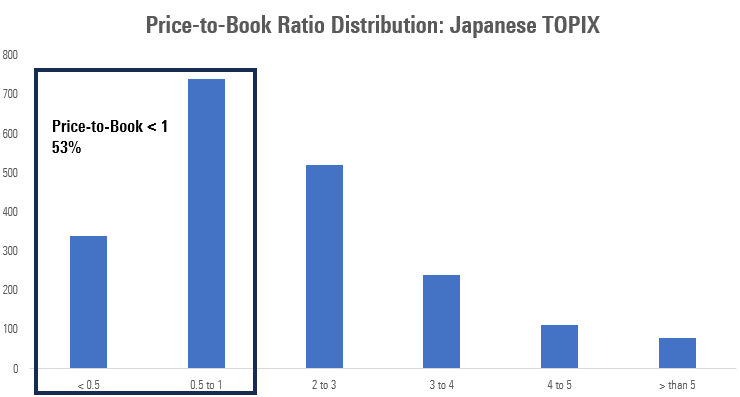

Earlier this year, the Tokyo Stock Exchange (TSE) formally “ordered” all listed companies trading at below book value to raise their price-to-book multiples above 1x—or publish a plan to do so—otherwise they risk being delisted.

Price-to-book is a valuation metric that compares a company’s stock price to its book value per share. The simple detail to know: If a company’s price-to-book ratio is below one, the market is valuing a company at less than its assets are worth.

This was a significant statement by the TSE—and it made clear that shareholders would be a priority going forward.

The TSE noted that more than 50% of listed companies traded below 1x price-to-book.

Exhibit 2

Source: Schroders, Bloomberg.

This is an anomaly globally. By comparison, only 5% of S&P 500 companies trade at price-to-book values of less than one and zero companies trade below 0.5.

When you think about valuations this low, it’s fair to assume many of these companies have the proverbial “hair on them.” This is likely true in some cases, but there’s also recognizable global brands that fall into this group like Toyota, Mitsubishi, and Honda—which collectively represent some $2 trillion in market capitalization.

The question becomes: How do you make book values increase?

The TSE specifically requested steps such as “pushing forward investment in R&D (research & development) and human capital that leads to the creation of intellectual property and intangible assets that contribute to sustainable growth, investment in equipment and facilities, and business portfolio restructuring.”

That sounds nice. However, it’s not exactly clear if it will directly translate into value for shareholders. In some cases, maybe it will—in others, maybe not.

Another method the TSE is pushing: increasing direct returns to shareholders, either via dividends or buybacks. This mandate could hold a lot more promise.

The percentage of companies that are “net cash” (i.e., whose cash on their balance sheets are greater than their liabilities) is 50%. That gives those companies the optionality to invest in their business or increase capital returns to shareholders. Perhaps both.

Reforms Spark Investor Interest

One simple idea about investing: capital tends to flow where it will be treated best.

Japan becoming serious about reform has sent the signal to investors that their capital will likely be treated better going forward. This doesn’t guarantee positive or strong returns, but it does suggest confidence at the very least.

One notable investor who has gained confidence in Japan? Warren Buffett.

Buffett has taken a major stake in five Japanese trading companies—which dabble in everything from auto parts to fish—and operate much like Berkshire Hathaway as diversified holding companies.

When asked about Japan at Berkshire’s annual meeting earlier this year, he had this say:

“We’ll just keep looking for more opportunities in Japan.”

To be clear, pointing out where Buffett’s investing is always interesting, but it’s also anecdotal. His investments should not serve as someone else’s due diligence.

Inflation Is Different in Japan

One other interesting point in Japan: Inflation might be a good thing.

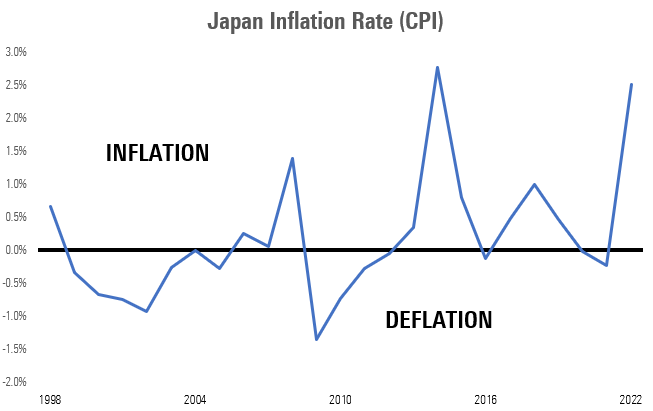

Unlike the rest of the developed world, where inflation has been met with a swift policy response (translation: increasing interest rates), Japan has spent considerable time over the past few decades batting the opposite problem: deflation.

Exhibit 3

Source: The World Bank

Deflation leads companies and consumers to delay investment and put off purchases. There’s little point buying something now if it will be cheaper tomorrow.

By contrast, moderate inflation gives companies the confidence to invest for the future—and also spurs consumers to spend.

Prices Responding

Japanese shares are flourishing this year.

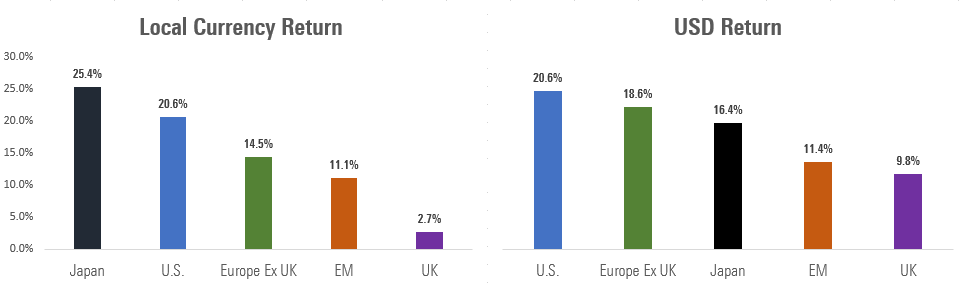

In May, major equity indexes—the Tokyo Stock Price Index (TOPIX) and the Nikkei 225—both hit their highest levels since 1989. Gains for Japanese equities have outpaced other developed markets, though the performance is not fully appreciated because a weaker yen has reduced those gains for overseas investors.

Japan has outperformed the U.S. and most of Europe in local currency, but when those returns are translated into dollars or euros, the performance is not quite as strong.

Exhibit 4

Source: Morningstar Direct. Data as 7/31/2023. Indexes shown are unmanaged and not available for direct investment.

Japan in a Portfolio?

The market is warming up to Japan—and rightfully so—as they’ve been serious about reform.

Buffett’s investment is an obvious example. Another would be a recent front page article in the Wall Street Journal on Japan’s improving fundamentals.

But there’s a certain irony about an investment idea that shows up on page 1—prices begin to reflect good news.

And there’s an old investing maxim that you don’t want to be chasing the investment discussed on page 1, rather, you’re better served focusing on the page 8 story that has the potential to move to page 1.

Obviously, that’s easier said than done.

But the logic is sound and captures the value of a contrarian mindset, which is a key part of our investing framework. We tend to be attracted to asset classes that are unloved by the market.

If everyone loves an asset—prices reflect that optimism—leaving less opportunity going forward.

Specific to Morningstar Wealth, Japan’s been a market we’ve held exposure for several years. The governance improvements have been a large part of our thesis. But now, that thesis is being adopted in larger quantities.

As a result, Morningstar—while still holding exposure—is beginning to dial some of it back.

We’re not doing this because the opportunity has left. Rather, it’s a function of our investment process, which includes evaluating contrarian indicators. When an asset class begins to become more consensus, we like to reduce our exposure.

Again, we do believe opportunity remains. One specific example? Capital returns. Companies—to date—have been reluctant to act on returning the cash held on balance sheets. Inflation could be the spark that causes them to act.

Cash sitting on a balance sheet when there’s no inflation holds its purchasing power—it’s not a major problem. But if inflation is higher and stickier, cash becomes expensive to hold, because it will lose purchasing power. Japan’s inflation path and how companies react is a story worth watching.

Japan is less contrarian than a few years ago, but there’s still an interesting investment case for a country that had been written off after decades of underperformance.