(Bloomberg) - It was an irresistible pitch. Give us your money, executives at Ray Dalio’s Bridgewater Associates and other hedge funds said, and we’ll funnel it into a money-minting, sure-thing strategy for the long haul. But now, after five years of sub-par returns, many of the institutional investors who sunk large sums into risk-parity funds, as they’re known, are demanding the money back.

Investors including public pensions in New Mexico, Oregon and Ohio have yanked out cash, slashing the size of the funds by an estimated $70 billion from their peak three years ago. For many, the pleas from firms for more time — that the next decade in markets is unlikely to resemble the last — ring hollow.

“It’s been disappointing for a long time,” said Eileen Neill, managing director at Verus Investments, an adviser to New Mexico’s roughly $17 billion public employee pension, which axed its risk-parity allocation in December. “The only time risk parity was really successful was at the time of the Great Financial Crisis and that was really its heyday.”

The lackluster run through the post-pandemic booms and busts has rattled faith in an allocation method pioneered by Dalio, who built Bridgewater into the world’s largest hedge fund. The strategy focuses on diversification across assets based on how volatile each is, and often uses leverage to optimize returns relative to the risks taken.

It flourished after the 2008 financial crisis as investors sought a way to protect themselves from the next big cataclysm. But as investors went on to plow back into stocks, they lagged in the up years. Then when markets cracked in 2022 — pummeling safe assets like US Treasuries — they were hit even harder.

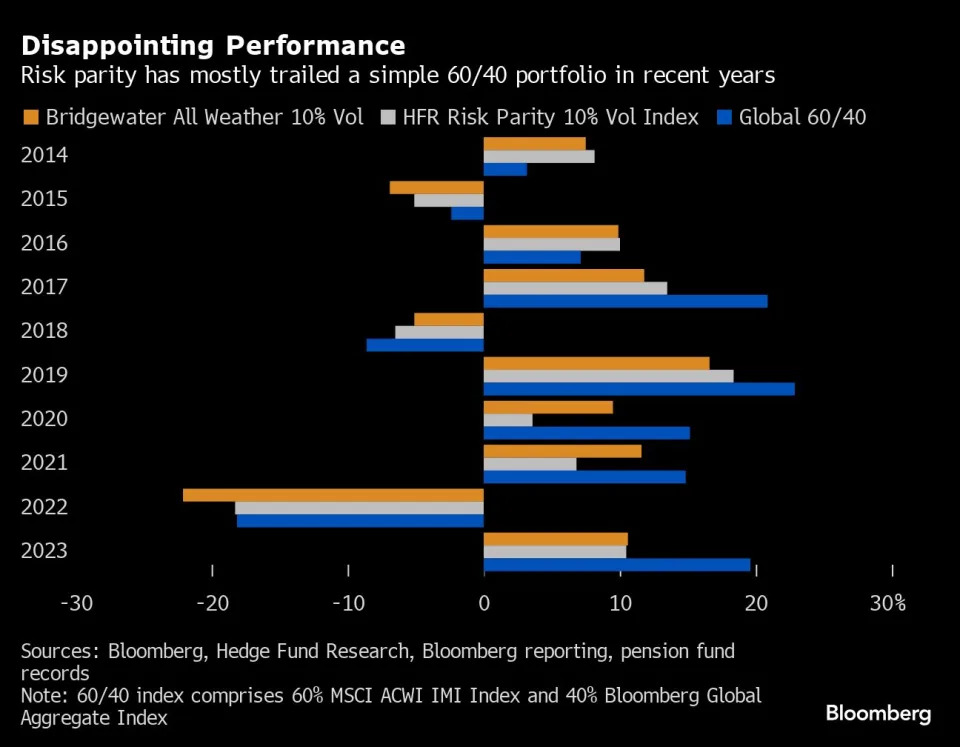

All told, risk parity funds have lagged global 60/40 funds every year since 2019, according to a broad index of the industry.

That’s driven investors to pull out cash, cutting the amount in such funds to about $90 billion by the end of 2023 from a peak of about $160 billion in 2021, according to Verus estimates compiled from eVestment data.

First launched in 1996 to manage Dalio’s trust assets, it was billed as a way to use deep economic research to craft the best possible portfolio, instead of trying to call the next big thing.

Rather than pile on risk to chase big returns, the strategy generally involves diversifying across a broader array of assets like commodities and bonds and making each an equal driver of the portfolio’s volatility. To keep the risks balanced, the exposures can be dialed up or down based on how much prices are swinging around, making the strategy Wall Street’s favorite scapegoat in a selloff.

A Tough Environment

To the strategy’s proponents, the decision to bail just as stock prices hit new records reflects a classic investing error.

“That really is reasoning from the past decade, which I will claim is more exceptional,” said Otto van Hemert, director of core strategies at Man AHL, which runs about $15 billion in risk parity.

That period was marked by low rates that for much of the time elevated stocks and bonds. Risk parity delivered positive returns but, almost by default, not as much as simple portfolios that put more in shares. Then when the Federal Reserve started raising interest rates in 2022, bonds tumbled before most models were able to react. Many funds saw volatility surge beyond their target levels or even the highs seen during the last financial crisis, according to Markov Processes International, an analytics company.

In a September presentation to the Indiana Public Retirement System, Bridgewater, the largest risk-parity manager, acknowledged that its All Weather fund has dipped below its expected returns. But the firm said it remains a superior way of allocating cash along a decade-long horizon, especially given the risk that stock gains will stall.

“Important secular forces that helped create the great equity run are fading,” according to the slides released by Indiana, which has kept its 20% allocation to risk parity.

All Weather’s most popular iteration, which targets 10% volatility, lost 22% in 2022, the slides show, lagging most peers. That appears to be because it is less reactive to short-term market swings and correlation changes, according to Michael Markov of Markov Processes.

Bridgewater declined to comment.

Money managers have started retooling the strategy away from its origins as an almost passive, long-term approach. Fidelity Investments launched a risk-parity fund in 2022 that can put on active trades to exploit market dislocations and also takes the market regime into account when tweaking exposures, says co-portfolio manager Christopher Kelliher.

At Man AHL, where the Target Risk fund has beat the HFR index — a measure of its peers — every year since its 2014 inception, van Hemert says the key is to be more reactive to changing market risks. That means boosting exposures more when markets are calm and even mostly holding cash in the rockiest times.

‘Diversification’s Nemesis’

Even so, risk parity is facing stiff competition from other corners of Wall Street, such as private-credit funds and superstar hedge funds that have delivered steady returns year after year.

“If I’m going to have 6% or 8% of my portfolio in something else, I’d rather that something else be a bucket of really good performing hedge funds,” said Michael Shackelford, chief investment officer at the Public Employees Retirement Association of New Mexico, which cut its risk-parity allocation in December.

In Oregon, the state’s investment council came to a similar conclusion. By July 2020, it had shifted more than $1 billion into risk-parity funds run by Bridgewater, Man Group and PanAgora Asset Management. But in late 2022 it reversed course, eliminating its investments in risk parity after the category lost about 6% a year. PanAgora didn’t respond to requests for comment.

To the strategy’s advocates, the move may prove short-sighted given lofty stock valuations while bonds are offering the highest yields in years.

“Diversification’s nemesis is FOMO—by definition you’re always going to have some regret,” said Jordan Brooks of AQR Capital Management, which runs $13.7 billion in risk parity investments. “It’s investors’ job at the end of the day not to look backward but forward to what’s the best portfolio to navigate the next decade.”

By Justina Lee

With assistance from Katherine Burton and Sam Potter