Perot kept a lot for the dynasty and didn’t keep track of what he gave away. With $80 billion at stake, Buffett’s promise means something different.

A lot of billionaires and mega-millionaires love the Giving Pledge that Warren Buffett and Bill Gates set up a decade ago.

But even they’re split between giving their wealth away and keeping it for dynastic purposes. And as you move up the scale, the philanthropic vow evidently becomes less attractive.

It’s only when you reach the absolute top that joining the club becomes meaningful, in large part because the numbers get so big that blood bonds no longer matter.

Any wealth manager who wants to work with the kind of clients who leave a lot of money behind needs to understand the way these priorities play out.

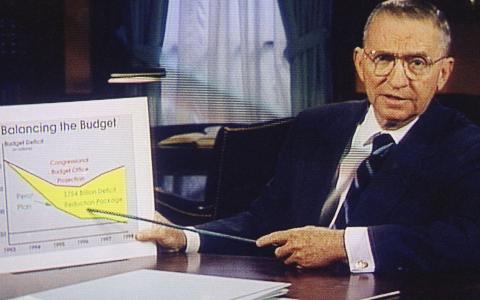

Just look at how Ross Perot allocated his fortune. He gave away substantial amounts over his lifetime and now his kids are undoubtedly set up for life as well.

But unlike Buffett and Gates, Perot didn’t feel the urge to commit years or decades in advance.

He deployed his billions in response to what he saw in the world around him. Where he wanted to step up, he stepped up. Otherwise, he conserved his cash for later.

Most truly wealthy people are like that. They give, they save and sometimes they spend.

Math behind the Pledge

Everyone who’s signed the Giving Pledge has noble objectives in mind. It’s great to try to make the world a better place.

But dig through the numbers and most of the Americans on the list are relatively low on the ultra-ultra-high-net-worth scale, with only a few rising above $3-5 billion in assets.

That’s still an awful lot of money when you’re committing to give half of it away in your lifetime. However, it’s still the kind of cash that generates at least $60 million a year in rock-solid Treasury debt and a whole lot more in the stock market.

Cutting that principal in half reduces the income to a mere $30 million. If the behavioral economists are right, that’s enough coming in to make six households feel rich.

Most of these families came from middle to upper middle class roots. They don’t envision the kids and grandkids collecting mansions.

Even at $1 billion, half of the income can easily fund two kids in perpetuity. If you’ve got a big family, you’re naturally going to want to keep more in reserve.

Perot had five kids. He wasn’t going to make any vast or binding commitments until he knew they were all taken care of.

Of course, it’s all relative. Perot easily made $10 billion in his lifetime bringing computing to Texas. His museum and active family foundations contain about $200 million of that money now.

That’s 2% of his lifetime wealth, a long way from half.

Now take a look at Buffett for comparison. Nice guy, gives away a lot of Berkshire Hathaway stock to every charity that catches his eye.

With three kids and only two grandkids, he could get away with leaving them only a fraction of his $84 billion in current wealth and donate the rest.

They could live in perpetual luxury with well under $2 billion. Everything else is play money.

Buffett could boost his pledge to 98% of his fortune and leave a dynasty behind. Bill Gates is in a similar place with his plan to give 95% of his lifetime worth away.

Similar logic applies with Larry Ellison, MacKenzie Bezos, Mark Zuckerberg and Mike Bloomberg. All are at the top of the pyramid with more than $50 billion apiece.

But below that rarefied level, most truly big billionaires aren’t signing up until you get back down to that $3-5 billion zone.

Some are already in the first stage of dynastic spread like the Waltons or the Mars heirs. They’re already at least one generation from the original wealth creation event and are now living on the income.

Their fortunes aren’t going to get any bigger. At best, with careful management, they’ll persist into the next century, but that’s a matter of how fast they get spent down.

Cutting a fortune in half automatically accelerates that process. While many of these people are extremely philanthropic, their donations are often opportunistic and not programmed by any external mandate.

They want to stay flexible to preserve their fortunes for their lifetime and as long as they can beyond that point. Think of retirees, negotiating the distribution phase only on a much grander scale.

It’s about wealth preservation first. Perot is a great example of this.

He was worth about $4 billion back in 1999. He died worth an estimated $4.1 billion.

That 1999 fortune invested in the stock market would be worth at least $6 billion today.

Maybe he spent all the income on himself because he found $100 million a year in toys to buy over the intervening time period. Sure, but not even Larry Ellison can spend that way without sending shockwaves through the luxury markets.

More likely, he gave a lot of that $2 billion in income away. We didn’t hear about it because the grants were small, local and personal.

Last tax year his foundations and museum took in $22 million in grants. Most of that was probably from him.

Beyond that, he kept his powder dry and his checkbook open. After all, you never know when you might decide to run for president.

Structured and unstructured agendas

But again, this is down in the $4 billion zone. A lot of self-made multi-billionaires use their money to directly fund their personal visions of society and where the world should go.

Think of the Koch brothers with their network of political donations and think tanks. They donate billions to outside causes but the real work goes on inside the family foundations.

As it happens, the Koch math works better investing money today trying to eliminate estate tax burdens tomorrow. A lot of their agenda revolves around that principle.

The Google founders spend a lot of their money on moon shot technologies of tomorrow: immortality, space travel and so on. So does Jeff Bezos.

They’re not in the Pledge club because they’re already reinvesting their fortunes in personal projects. It isn’t “venture capitalism” because there’s very little incentive to incubate these companies in pursuit of an exit.

Making money is nice in Silicon Valley, but building rockets and running newspapers is really more about spending it.

After all, all the money in the world is just numbers unless you can use a little of it to run for president once in a lifetime. Perot got that.

The Koch brothers are more interested in nudging policy. (It’s hard to ignore the way George Soros isn’t in the Pledge club either.)

Previous generations might have raced cars or yachts, explored blank spots on the map. This is what the mega fortunes of today do.

After all, they could give 70-95% of it away and the kids are still set for life. Everything else is about ambition and personal bliss.

Whatever else you say, Ross Perot followed those calls in his life. He didn’t need to join a club to do it.