(Bloomberg) The 2008 Great Recession was more an ideological awakening than an economic crisis for some. Ashleigh Schap's hometown of Houston escaped the worst of the maelstrom that ravaged large parts of the U.S., her parents kept their jobs, and the house she was living in retained most of its value. She had little reason to imagine the wheels would come off America’s capitalist machine.

Yet the events of that year left a lasting impression on the teenager. The financial crisis and its aftershocks, which she read about on blogs and discussed with her classmates, made her realize that good times don’t last forever. More important to what she would do later in life, she says they left her with a distaste for a lopsided financial system that benefits and protects those at the top at the expense of those at the bottom.

“I’m from Texas. My family is conservative and capitalist,” she says. “And this was the first evidence I had seen that the ideas of growth at all times, that the cream always rises to the top, and that markets will always be efficient, failed.”

It would be five more years before Schap would discover Bitcoin—a key moment in her growing rebellion against existing political and financial structures—and five more before she would work on creating what she saw as a fairer financial order. She would also diverge politically from her family. “I don’t talk to them about politics anymore,” says Schap, who’s now 27.

Her path from the high school chess club to crypto rebel was far from inevitable. Even before graduating in 2014 from the University of Texas at Austin, she joined JPMorgan Chase & Co. in Dallas as an analyst in the company’s business for wealthy clients. She says she spent less than half a year there, moved to New York, knocked around a fintech firm and a family office for a while, and eventually, in April 2018, landed on the outermost fringes of finance at MakerDAO.

The key to MakerDAO is in its name: DAO stands for decentralized autonomous organization. It’s an online platform for creating digital dollars, or so-called stablecoins, and generating loans secured by crypto tokens—all run by a blockchain-based computer program and free of oversight by any central party, such as, say, a government.

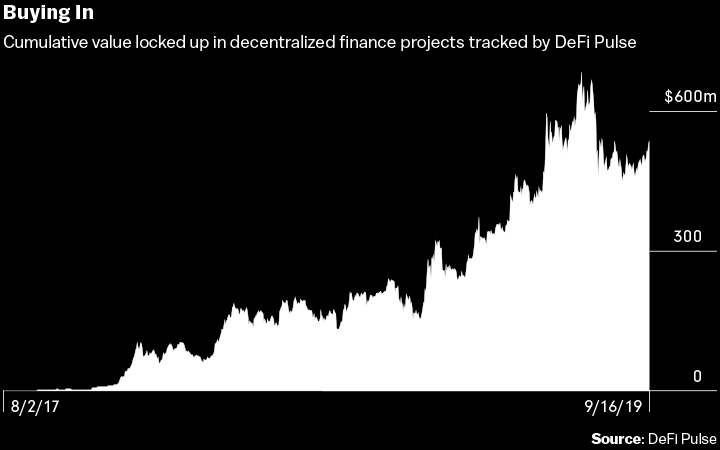

MakerDAO is the most important player in the fast-growing movement known as decentralized finance. #DeFi—widely known by its Twitter hashtag—aims to create a financial world where everything from loans to investments is readily available to anyone without having to go through gatekeepers who decide who gets to play or intermediaries who charge fees at every turn.

It was a world in which Schap felt at home. In her early 20s, the online game World of Warcraft had introduced her to Bitcoin: She needed it to buy an accessory for her avatar. She bought five Bitcoin tokens in February 2013 (and then lost the same number a year later when the Mt. Gox exchange froze withdrawals following a hack of its systems). Decentralized finance is a natural outgrowth of crypto’s ideology. The DeFi movement is small; it’s almost exclusively the preserve of crypto utopians, many of them clustered around San Francisco. Its critics—and there are many—say it’s a wild experiment run by people ill-equipped to be designing financial products.

“The technology might be interesting for more efficient delivery of financial services, but the naiveté and lack of knowledge of financial history seem shocking to me,” says Richard Bernstein, founder of Richard Bernstein Advisors LLC and a former chief investment strategist at Merrill Lynch & Co. “There’s this tear-down-the-house mentality, with minimal understanding of why financial regulation even exists.”

Schap says she’s no financial ingénue. “I left the traditional financial world for a reason, not because I was not being paid enough, but because I wanted to see what we could do with this new technology and how far we could push it,” she says. “I’m not some crazy renegade. I’m quite the opposite. Blockchain has the potential to create a fairer financial system than we currently have, with more flexibility and greater opportunities to access credit.”

Indeed, the ideas behind decentralized finance could have broad resonance beyond crypto circles. Popular uprisings from the global Occupy movement to the Hong Kong protests are driven by a young population pushing back against societal injustices and existing power structures, including in finance.

Working for MakerDAO, her hair dyed pink, her workstation a stone’s throw from the New York Stock Exchange, Schap had completely transitioned to the financial resistance. She says she loved that MakerDAO was the antithesis of a corporate giant like JPMorgan—less a corporation than a cooperative, a commune for the digital age with developers and entrepreneurs around the world collaborating on an exciting new project.

And yet unbeknownst to Schap, even by the time she joined MakerDAO, a rebellion was brewing within the rebellion. The infighting—in which Schap would become an accidental combatant—revolved around how decentralized financial services can ever really be. MakerDAO’s founder, Rune Christensen, had come to believe it was time to move away from crypto anarchism and integrate the project into the existing financial system. Others, including Chief Technology Officer Andy Milenius and Schap, saw such a move as a betrayal of the ideals they cherished.

In an account of the startup’s ideological battles that Milenius shared on the company’s chat server in early April, he said Christensen, in trying to force his vision on what had been a loose coalition of developers and businesspeople, gave them an ultimatum to get on board with his agenda or leave. While Milenius’s post said numerous staffers were uncomfortable with Christensen’s power play, Schap was the only employee he mentioned by name.

As would soon become clear, her days at MakerDAO were numbered.

Schap’s studies at UT Austin weren’t a natural launchpad for a career in finance. As a philosophy major, with a minor in French, she says she told a JPMorgan recruiter her liberal arts education taught her how to think through problems. The job didn’t suit her in the end. “I didn’t feel like what we were doing was moving the needle,” she says. “We were collecting all these fees, but I thought we were really overpaid. It wasn’t exactly rocket science.”

Schap felt increasingly pulled to the edges of finance. There just hadn’t been many opportunities to make a career in the crypto industry, she says, during the five years she’d spent in traditional finance. But by last year, she says, she felt qualified enough, and bored enough, to take advantage of an opportunity that arose to join MakerDAO. Schap worked in business development, and what began as a jack-of-all-trades job soon morphed into a singular focus on delivering the most ambitious phase of the project: creating a stablecoin backed by multiple types of collateral. She says she worked on finding partners that could supply collateral to the MakerDAO system.

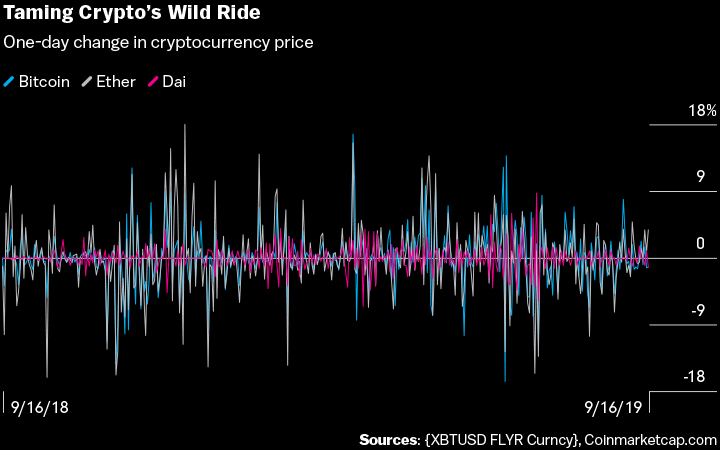

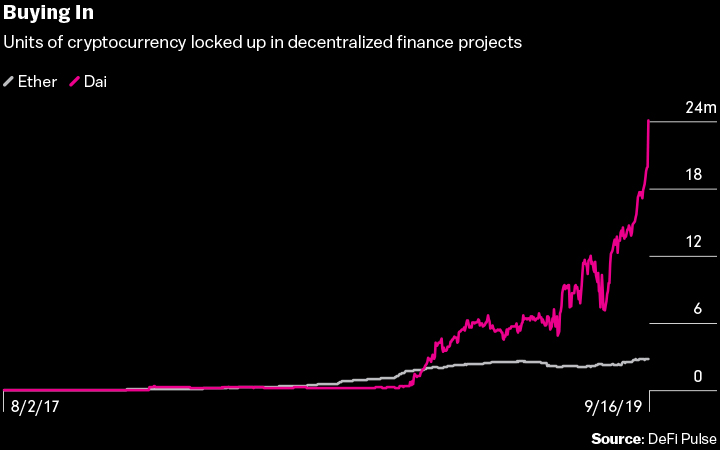

MakerDAO’s stablecoin, Dai, is pegged to the dollar and, in its current iteration, backed by the cryptocurrency Ether. There are about $82 million worth of Dai in circulation as of Sept. 19. Launched in late 2017, Dai was one of the first of what’s become a flurry of virtual currencies designed to avoid large price swings.

Stablecoins like Dai can be used as a hedge against volatility. Ether peaked at more than $1,400 each at the beginning of 2018, only to fall to $84 at the end of the year and then to trade at $175 at the beginning of October. Dai can also be used to pay for things. Users of Dai claim to have bought cars and paid their employees’ salaries with the currency. MakerDAO says some payments companies such as Wirex Ltd. allow customers to use the token to facilitate the movement of funds between cryptocurrencies and traditional money.

The Dai token also enables lending. Dai is created when holders of Ether send their crypto to a blockchain-based computer program developed by MakerDAO and open what’s known as a collateralized debt position. The CDP then issues a loan to Ether holders in Dai. The loan is smaller than the amount of Ether posted to maintain overcollateralization in case of market stress.

Dai, sold on exchanges such as Coinbase, is also widely used in other DeFi projects. Advocates of decentralized finance aspire to do more than just replicate the current system: They see a world in which DeFi projects collaborate to create business models and products that couldn’t exist without blockchain technology.

“Imagine being able to develop new financial markets that previously needed a multimillion-dollar bespoke contract designed by an investment bank, but with a few points and clicks,” says Joey Krug, a DeFi entrepreneur and co-chief investment officer at Pantera Capital, the first U.S. investment firm focused on Bitcoin.

MakerDAO has a second token, MKR. A bit like shares in a public company, it gives holders voting rights on such matters as how much collateral is required to borrow Dai. Holders are rewarded for sound management with money drawn from fees charged to borrowers. The value of these tokens could be diluted if loans aren’t repaid. There are $450 million worth of MKR outstanding.

Schap says that if the MakerDAO system works as envisioned, it will be like a decentralized bank, taking deposits, facilitating lending, and managing risks. It also functions like a central bank in that it sets interest rates (in the form of what is called a stability fee, which is designed to help Dai track the dollar).

Before division and disenchantment set in at MakerDAO, Schap says, she felt she was involved in a startup that wasn’t only reinventing finance but also creating a new type of corporate structure—impromptu brainstorming, a flat organization, ideas flying in from people regardless of job title or area of responsibility. All this, she says she believed in those early days, wasn’t a function of good personal chemistry; it was Maker’s DNA.

Or maybe it wasn’t. Her growing unease was thinly veiled in a series of tweets she sent on her one-year anniversary there. One of them said: “I believe in a global, borderless, decentralized money. I believe in transparency and open governance. I also believe that we are human beings, we are flawed, and we have to set aside our selfish desires to make these things work. Because this work is worth doing. This matters.”

A few weeks earlier, Christensen, who co-founded MakerDAO in 2014, had issued his ultimatum in true counterculture style. Christensen is a 28-year-old Danish entrepreneur. While still in college, the Mandarin speaker co-founded a company that recruited European teachers to work in China. Taking inspiration from the sci-fi film The Matrix, he gave his MakerDAO development team a choice. The red pill: Get on board with Christensen’s vision, whose “main focus,” as Milenius described it in his post, “was on government compliance and integration of Maker into the existing global financial system.” The blue pill: If you feel differently, finish your work and then leave.

Taking the red pill doesn’t mean you’re a sellout to mainstream finance, Christensen says: “I reject the idea that I’m not an idealist.” He says he believes that startups like MakerDAO have few examples to follow, and to succeed in a fast-paced industry, they need to adapt to the real world.

“The big journey and challenge is how to deliver this vision,” he says. “It’s quite easy to write a white paper and code, but to get a real live decentralized finance system going, you need to deal with challenges like regulation and how to integrate with the establishment.” In his view, the DAO-like setup that Schap cherished led to a “tyranny of structurelessness.”

MakerDAO last year established the Maker Foundation. Designed to make the Dai credit system a success, it was intended to formalize the structure. As of mid-September, the foundation was still in the process of recruiting a professional board of directors, according to Christensen.

In response to his ultimatum, Schap and some like-minded employees proposed a third way, which became known as the “purple pill.” They were seeking a compromise to preserve MakerDAO’s decentralization ethos and ensure that its resources would be used to finance as broad a spectrum of DeFi projects as possible. “If you’re going to build a new system, it’s going to require selfless thinking and be designed so that there’s not one company or entity that gets all the rewards,” says Schap. “You need to remove the advantages of being at the top, and that is hard to do: If we build something, we feel we need to get our pound of flesh.”

Christensen, according to Milenius’s post, viewed the purple pill discussion as an uprising. Milenius said numerous purple pill partisans were fired. Schap was fired at the end of April. She says the reason given for her dismissal was violation of a nonsolicitation clause, something she denies. A MakerDAO spokesperson declined to comment.

Milenius, 27, who stepped down as CTO shortly before he wrote his treatise, says the struggles at MakerDAO are representative of a wider conflict that pervades the crypto community—a battle between those who see blockchain technology as a means to entirely reimagine the financial world and those who see it simply as a useful tool to make that world more efficient. “The blockchain community has always been starkly divided between those with a reform agenda and those with a radical vision for a new way to live,” he says. “After the events of this past spring, it has become clear to me that Maker now exclusively falls into the former camp.”

For Christensen, the next phase of the project is about increasing users and profits. He says he’s considering whether the Maker Foundation should obtain a broker-dealer license or acquire a licensed brokerage firm so the MakerDAO system can accept collateral from the real world to back Dai. “The future is not about making Maker work, but about figuring out how the ecosystem becomes as sprawling as it’s able to and how it can make money,” he says. “There is so much to be done before the crypto ecosystem becomes this big self-sustaining economy.”

Schap says she was surprised to find herself at the center of the MakerDAO storm. “I somehow ended up being the poster child of this perceived mutiny,” she says. “The reality was quite a bit different. It wasn’t me leading. There was no coup.”

After losing her job at MakerDAO, Schap headed to Egypt for some downtime. At Dahab, on the Red Sea, the longtime scuba diver tried something more adventurous: learning to free dive down 66 feet (20 meters). Schap says she relished the mental challenge of “calming your mind and pushing past the urge to breathe or swim up.” From Egypt, she went to Berlin, a hub for blockchain developers, where she advised some DeFi projects.

Schap says her experience at MakerDAO has strengthened, not broken, her conviction that decentralized financial services are necessary and worthwhile. She says she hopes MakerDAO prospers. She put a year of her life into it, after all, and she holds some MKR tokens. But she remains unconvinced that platforms such as MakerDAO need to be regulated.

Decentralized finance is dismissed as little more than a distraction by vast swaths of the financial community, so MakerDAO’s next steps matter: It’s the largest and most closely watched DeFi project. It has a significant bearing on the broader $220 billion crypto market, says Robert Leshner, CEO of Compound, a virtual-currency money market.

Leshner says MakerDAO and DeFi more generally are helping to provide an answer to the question that hangs over crypto. “After the bubble, then crash, of 2017 and 2018, it’s natural to ask, ‘What do we use this stuff for?’ ” he says. “ [DeFi] is the first legitimate answer to the question. DeFi is starting to have its moment because it’s the next chapter for crypto.”

As for Schap, decentralization has become something of a life goal. She says she’s now working on her own DeFi startup with friends and will split her time between Berlin and New York. “I don’t think Maker will ultimately make or break DeFi,” she says. “It’s already helped to make it. And I don’t think it’s possible, even if Maker were to fail, for this train to stop rolling.”