WHEN AN OUTBREAK strikes, it is natural to become leery of hopping on an airplane. It is even more alarming when two serious viruses are circulating at once.

The world is gripped by a new coronavirus that started in China and has since moved into more than two dozen other countries, including the United States. Meanwhile, it is also flu season, which so far has caused 10,000 deaths in the U.S.

Major airports have begun screening passengers for the coronavirus, and more than three dozen airlines—including Delta, American and United—have cut their flights to mainland China. But those measures may not provide much solace to anyone who has to board a flight.

After all, you can avoid the person who is sneezing in line at Cinnabon, but you’re more or less left to fate once you’ve strapped on that seatbelt inside a flying metal canister.

While there is still much to learn about the Wuhan outbreak, scientists do know a bit about similar coronaviruses and other respiratory illnesses like influenza. So how do those viruses spread—and specifically on airplanes? And how serious is the coronavirus threat compared to the likes of influenza? Let’s take a look.

How do respiratory illnesses spread in general?

If you’ve ever sneezed into your arm or steered clear of an office colleague with a hacking cough, you already know the basics of how respiratory illnesses spread.

When an infected person coughs or sneezes, they shed droplets of saliva, mucus, or other bodily fluids. If any of those droplets fall on you—or if you touch them and then, say, touch your face—you can become infected as well.

These droplets are not affected by air flowing through a space, but instead fall fairly close to where they originate. According to Emily Landon, medical director of antimicrobial stewardship and infection control at the University of Chicago Medicine, the hospital’s guidelines for influenza define exposure as being within six feet of an infected person for 10 minutes or longer.

“Time and distance matters,” Landon says.

Respiratory illnesses can also be spread through the surfaces upon which the droplets land—like airplane seats and tray tables. How long those droplets last depends both on the droplet and the surface—mucus or saliva, porous or non-porous, for example. Viruses can vary dramatically in how long they last on surfaces, from hours to months.

There’s also evidence that respiratory viruses can be transmitted through the air in tiny, dry particles known as aerosols. But, according to Arnold Monto, professor of epidemiology and global public health at the University of Michigan, it’s not the major mechanism of transmission.

“To be sustained, to allow true aerosols, the virus has to be able to survive in that environment for the amount of time it’s exposed to drying,” he says. Viruses would rather be moist, and many fade from being infectious if left dry for too long.

What does that mean for airplanes?

The World Health Organization defines contact with an infected person as being seated within two rows of one another.

But people don’t just sit during flights, particularly ones lasting longer than a few hours. They visit the bathroom, stretch their legs, and grab items from the overhead bins. In fact, during the 2003 coronavirus outbreak of the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), a passenger aboard a flight from Hong Kong to Beijing infected people well outside the WHO’s two-row boundary. The New England Journal of Medicine noted that the WHO criteria “would have missed 45 percent of the patients with SARS.”

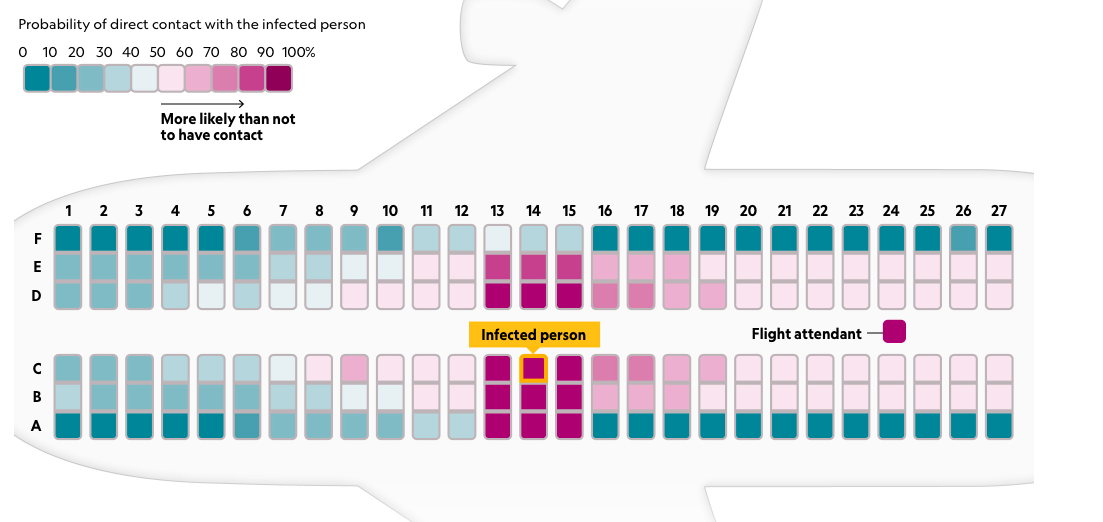

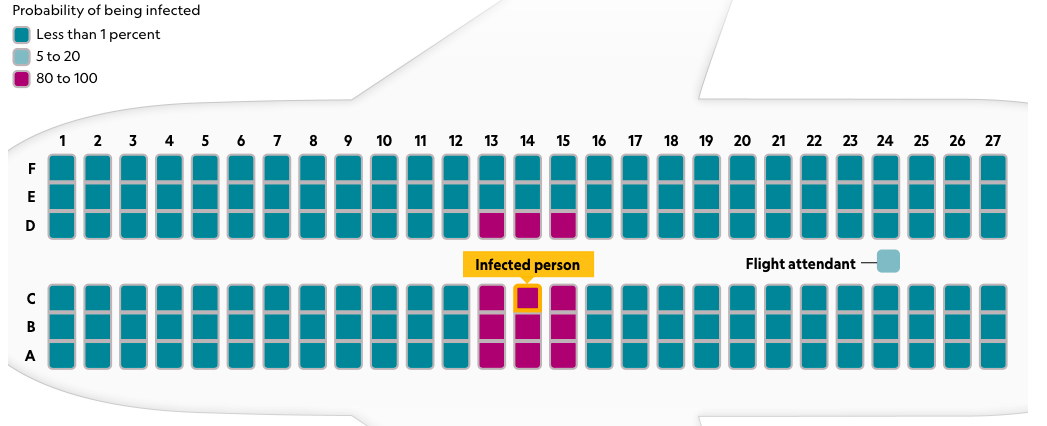

Inspired in part by that case, a team of public health researchers set out to study how random movements about the airplane cabin might change passengers’ probability of infection.

Passengers in window seats have the lowest likelihood of coming in contact with an infected person.

The “FlyHealthy Research Team” observed the behaviors of passengers and crew on 10 transcontinental U.S. flights of about three and a half to five hours. Led by Emory University's Vicki Stover Hertzberg and Howard Weiss, they not only looked at how people moved about the cabin, but also at how that affected the number and duration of their contacts with others. The team wanted to estimate how many close encounters might allow for transmission during transcontinental flights.

“Suppose you’re seated in an aisle seat or a middle seat and I walk by to go to the lavatory,” says Weiss, professor of biology and mathematics at Penn State University. “We’re going to be in close contact, meaning we’ll be within a meter. So if I’m infected, I could transmit to you...Ours was the first study to quantify this.”

As the study revealed in 2018, most passengers left their seat at some point—generally to use the restroom or check the overhead bins—during these medium-haul flights. Overall, 38 percent of passengers left their seats once and 24 percent more than once. Another 38 percent of people stayed in their seats throughout the entire flight.

This activity helps pinpoint the safest places to sit. The passengers who were least likely to get up were in window seats: only 43 percent moved around as opposed to 80 percent of people seated on the aisle.

Accordingly, window seat passengers had far fewer close encounters than people in other seats, averaging 12 contacts compared to the 58 and 64 respective contacts for passengers in middle and aisle seats.

Choosing a window seat and staying put clearly lowers your likelihood of coming into contact with an infectious disease. But, as you can see in the accompanying graphic, the team’s model shows that passengers in middle and aisle seats—even those that are within the WHO’s two-seat range—have a fairly low probability of getting infected.

Weiss says that’s because most contact people have on airplanes is relatively short.

“If you’re seated in an aisle seat, certainly there will be quite a few people moving past you, but they’ll be moving quickly,” Weiss says. “In aggregate, what we show is there’s quite a low probability of transmission to any particular passenger.”

The story changes if the ill person is a crew member. Because flight attendants spend much more time walking down the aisle and interacting with passengers, they are more likely to have additional—and longer—close encounters. As the study stated, a sick crew member has a probability of infecting 4.6 passengers, “thus, it is imperative that flight attendants not fly when they are ill.”

What does it mean for the new coronavirus?

As Weiss points out, we don’t know yet the preferred way that the new coronavirus transmits. It could be primarily through respiratory droplets, physical contact with saliva or diarrhea followed by oral consumption of viral material, or perhaps even aerosols.

He notes that this model doesn’t include the transmission of aerosols, though the FlyHealthy team hopes to research this topic in the future. In the study, the researchers also warn that this model cannot be directly extrapolated for long-haul flights or airplanes with more than one aisle.

Landon agrees that we don’t yet know how the coronavirus transmits, but believes the results of this study are applicable. All previous coronaviruses have transmitted through droplets, she notes, so it would be unusual if this new pathogen was different. And indeed, the new coronavirus is behaving much like SARS in many respects. Both are zoonotic, meaning they started in animals before jumping to humans, and both appear to have started in bats. The pair also transmit from human to human and have a long incubation period—up to 14 days for the Wuhan coronavirus, compared to about two for influenza—which means that people might be sick and transmitting the disease before symptoms show up.

With all that in mind, Landon suggests following the CDC guidance for infectious diseases when you’re on an airplane.

That includes washing your hands with regular soap or using an alcohol-based hand sanitizer after touching any surface—especially since there’s evidence that coronaviruses last longer on surfaces than other illnesses, around three to 12 hours.

You should also avoid touching your face and contact with coughing passengers by whatever means possible.

What’s worse, the coronavirus or influenza?

There are many ways to estimate the risk posed by a disease, but let’s focus on two numbers often used by public health researchers: the reproduction number and the case-fatality ratio.

The reproduction number—R0 or “r naught”—simply refers to the number of additional people that an infected person typically makes sick. Maia Majumder, a faculty member at Boston Children’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, has been tracking exactly that.

Her preliminary results indicate a transmissibility rate for the new coronavirus ranging from 2.0 to 3.1 people. That’s higher than influenza—1.3 to 1.8—but similar to SARS, which has a basic reproduction number in the 2 to 4 range. So, coronaviruses are slightly more prone to spreading between people.

The case-fatality ratio—or death-to-case ratio—is the number of people killed by disease divided by the number of people who catch it. Seasonal influenza, despite being considered a global scourge, technically kills a relatively small proportion of its cases, with a case-fatality ratio around 0.1 percent. The reason the flu is an annual public health emergency is because it infects boatloads of people—35.5 million in the U.S. across 2018 and 2019, which led to 490,000 hospitalizations and 34,200 deaths. That’s why health officials perpetually recommend that people receive a flu shot.

The case-fatality ratio also helps explain why public health agencies send up alerts over emerging outbreaks of coronaviruses. SARS had a case-fatality rate of 10 percent, about 100 times higher than influenza, and the rate for the new coronavirus is currently near 3 percent, which is on par with the 1918 Spanish influenza pandemic.

If SARS or the Wuhan coronavirus ever reached millions of people, it could be devastating. Unlike with influenza, Landon says, the entire human population is susceptible to this coronavirus because no one has ever had it before—and there is no specific treatment like a vaccine.

Health officials and the public are dependent on infection control, such as washing hands, reducing contact with afflicted individuals and quarantines. Monto suggests that these public health measures could make a difference in turning the tide against this coronavirus as they did with SARS.

“That’s the hope here, that it can be controlled by standard public health measures—because that’s what we’ve got,” he says. “With flu we have vaccines, a couple antivirals. We don’t have those for this coronavirus.”

This article originally appeared on National Geographic.