(Morningstar Investment Management) There's a concept in investing of "fighting the last war."

A quick summary of the concept would be:

- Investors experience a bad outcome,

- Investors emotionally anchor themselves to that outcome, and

- It prevents them from acting rationally going forward.

Last year was one of those bad outcomes—the stock market experienced its worst year in a decade—and investors are having a hard time shaking the feeling.

The market has rallied nearly 30% since October, which, in theory, means we’ve entered a new bull market. However, many people simply do not care—last year’s scars are still fresh.

Taking the pulse of institutional investors, many remain sanguine about the market’s prospects. According to the June Marquee QuickPoll, which surveyed nearly 900 institutional investors, only 3% of investors classify themselves as “bullish.”

Exhibit 1

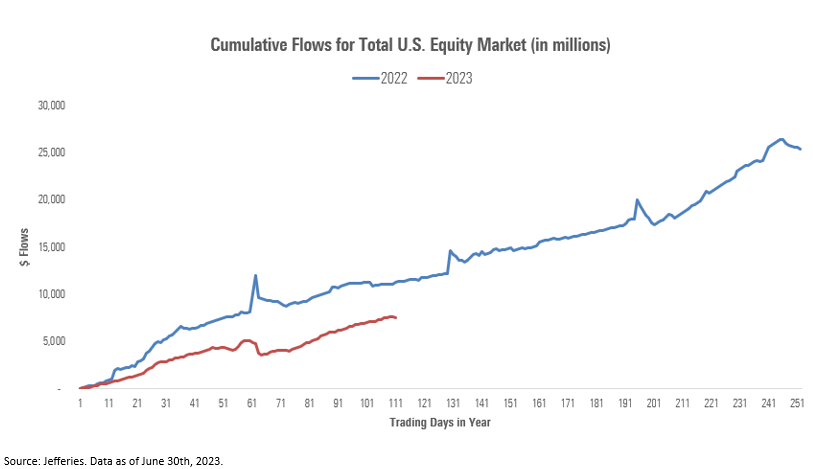

In short, many investors don’t appear to be putting much faith into this rally. We see this in equity flows, which remain subdued and well below last year’s pace.

Exhibit 2

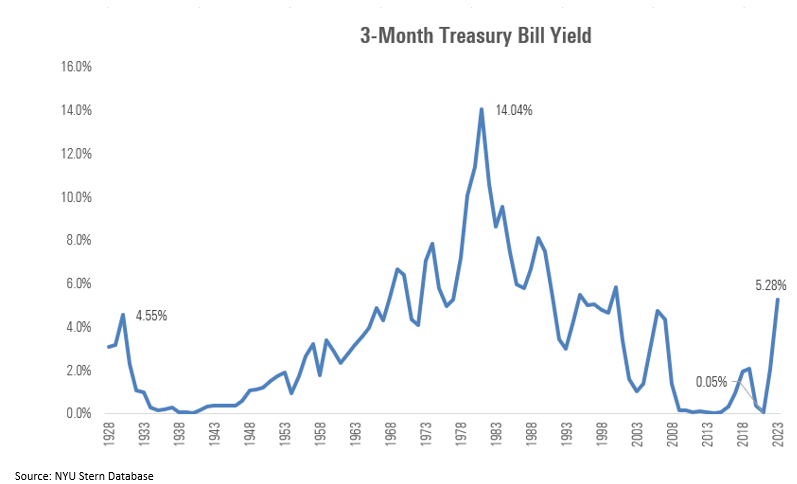

One point of contention: Cash is yielding more than it has in a decade—so are equities even worth the trouble?

We won’t bury the lede. The answer is still yes.

But it’s a fair question. Using 3-month Treasuries as a cash proxy, investors can earn more than 5% on cash. This is the highest yield since 1995.

Exhibit 3

Only two years ago, 3-month Treasuries were yielding nothing. The environment changed in a hurry.

Stating the obvious, it feels comfortable to earn 5% in cash while carrying a fraction of the risk of equities. But what feels comfortable is often not going to take you where you want to go.

While holding cash may make you feel good in the short term, the long-term track record of that decision could have a major negative impact.

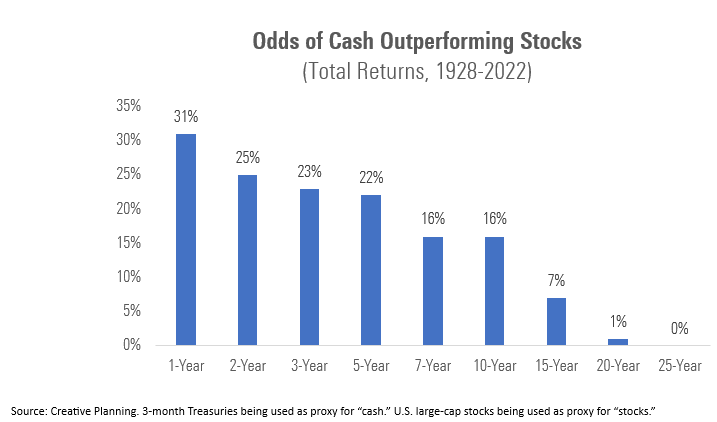

Since 1928, cash has beaten stocks 31% of the time over a one-year period. But as time goes on, the chance of cash beating stocks narrows significantly. In fact, there has never been a 25-year period where cash has outperformed the stock market.

Exhibit 4

This data isn’t particularly profound. The stock market goes up more often than it goes down, so more often than not stocks will outperform cash.

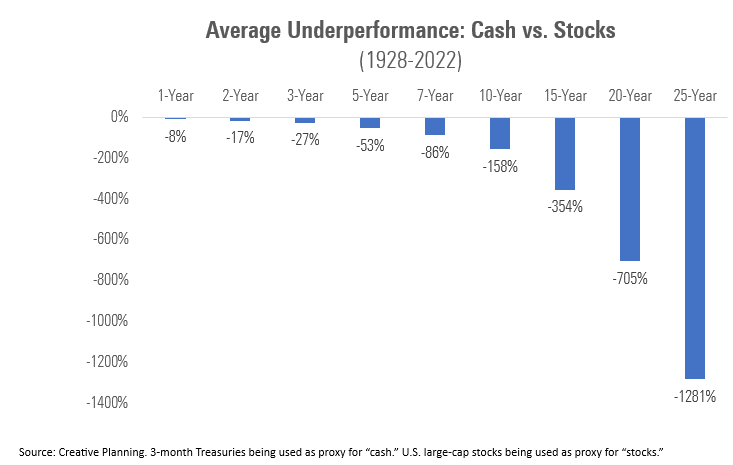

A bigger question is: What is it costing investors by sitting in cash?

In the short term, the opportunity cost is very little. On average, cash only underperforms the stock market by 8% over one-year periods. But the differential increases exponentially over time.

Over a five-year period, the difference between stocks and cash is more than 50%. Over 20 years, it’s more than 700%.

Exhibit 5

The lesson is clear: The opportunity cost of sitting in cash is huge and grows over time.

There are certainly caveats to make. Some investors have short-term cash needs—saving for a house, tuition payments, etc.—and that money should not be in the market. This is a welcome environment for those types of situations. But for those with longer time horizons, despite higher rates, cash should not be thought of as an equity substitute.

Investing is a game where success usually follows those who think using probabilities, rather than certainty.

There are no perfect allocations or times to invest in risk assets. The answer is only obvious with the benefit of hindsight. The best thing investors can do is figure out an allocation that works for them and avoid guessing what will happen based on your feelings.